Florence, South Carolina

+ + +

Services conform to the 1928 Book of Common Prayer

|

Anglican

Church of Our

Saviour

Florence, South Carolina + + + Services conform to the 1928 Book of Common Prayer |

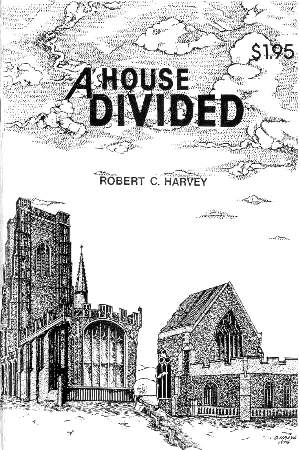

A House Divided

by Robert C. Harvey

Printed in the United States of America

Printing History:

1st Printing, July 1976

2nd Printing, Nov. 1976

3rd Printing, April 1977

4th Printing, July 1977

5th Printing, Nov. 1977

6th Printing, July 1978

7th Printing, Sept. 2003

"Mother Hive" from ACTIONS AND REACTIONS, copyright 1908 by

Rudyard

Kipling. Reprinted by permission

of Mrs. George Bambridge and Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Transcribed and

uploaded to the www with the author's

permission by Joe Sallenger,

Gofer-In-Chief for Church

of Our Saviour Anglican Catholic Church in Florence, South

Carolina.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. The Mother Hive

II. The Liberal Constitution

III. Decade knce in the Parish

IV. Disruption in the Church

V. The Undoing of the Seminaries

VI. The Bending of the Mind

VII. The Uses of Power

VIII. The New and Ugly Shape of Man

IX. An Inside Witness (A Statement by Robert M. Strippy)

X. An Outside Witness

XI. Predestination a la Marx and Freud

XII. What's to Be Done?

Letters and

Comments on Recent Books by

Robert C. Harvey

Five years before the outbreak of World War I -- and nearly ten years before the Russian Revolution -- Rudyard Kipling wrote a short story about the corruption and overthrow of a society. Like many political allegories, the tale was an animal story. The Mother Hive tells how a community of bees was infiltrated and destroyed by a wax moth who managed to get inside and lay her eggs.

Grey Sister (the wax moth) capitalized on the fact that the target hive was overcrowded, and that the stock had lost its vitality. She achieved her coup by lies, deceit and fraud. She arranged to get mentinside by creating a diversion at the gates. Once inside, she gathered a coterie of sympathizers -- the weak and dissident, who set no store by their own values or by those of the hive. Some of these were so giddy as to ascribe to the wax moth the virtues that are normal only to well-disciplined bees. These were a group that, in identifying with what was alien, not only lost the power to make distinction, but ultimately came to regard all distinction as discrimination. Other bees were so dissatisfied with their role as workers that they readily subscribed to Grey Sister's charge that the ancient and natural order of bees was unjust.

The first of these groups were the bleeding hearts. They were not revolutionaries by nature, but rather clung to the order of things. Still, their inability to believe in that order made it impossible for them to be what they were supposed to be, and consequently for the hive to be what a hive is supposed to be. It was only the second group who were the overthrowers, who actively turned against their own. Both, however, were turncoats. They were Grey Sister's falange of dissidents who brought about the hive's corruption and the destruction of its inhabitants.

When the aged Queen finally learned what was going on, she proceeded to the alighting-board and issued her swarming cry. The results are described in Kipling's words:

The roar which should follow the Call was wanting. They heard a broken grumble like the murmur of a falling tide.

"Swarm? What for? Catch me leaving a good bar-frame hive, with fixed foundations, for a rotten old oak out in the open where it may rain any minute! We're all right! It's a 'Patent Guaranteed Hive.' Why do they want to turn us out? Swarming be gummed! Swarming was invented to cheat a worker out of her proper comforts. Come on off to bed!" `01

The noise died out as the bees settled in empty cells for the night.

"You hear?" said the Queen. "I know the Hive."

"Quite between ourselves, I taught them that," cried the Wax-moth. "Wait until my principles develop and you'll see the light from a new quarter."

"You speak truth for once," the Queen said suddenly, for she recognized the Wax-moth. "That light will break into the top of the Hive. A Hot Smoke will follow it, and your children will not be able to hide in any crevice."

"Is it possible?" Melissa whispered. "I -- we have sometimes heard a legend like it."

"It is no legend," the old Queen answered, "I had it from my mother, and she had it from hers. After the Wax-moth has grown strong, a Shadow will fall across the gate; a Voice will speak from behind a Veil; there will be a Light, and Hot Smoke, and earthquakes, and those who live will see everything that they have done, all together in one place, burned up in one great fire." The old Queen was trying to tell what she had been told of the Bee Master's dealings with an infected hive in the apiary, two or three seasons ago; and, of course, from her point of view the affair was as important as the Day of Judgment.

"And then?" asked horrified Sacharissa.

"Then, I have heard that a little light will burn in a great darkness, and perhaps the world will begin again. Myself, I think not."

"Tut! Tut!" the Wax-moth cried. "You good, fat people always prophesy ruin if things don't go exactly your way. But I grant you there will be changes."

There were. When her eggs hatched, the wax was riddled with little tunnels, coated with the dirty clothes of the caterpillars. Flannelly lines ran through the honey-stores, the pollen-larders, the foundations, and, worst of all, through the babies in their cradles, till the Sweeper Guards spent half their time tossing out useless little corpses. The lines ended in a maze of sticky webbing on the face of the comb. The caterpillars could not stop spinning as they walked, and as they walked everywhere, they smarmed and garmed everything. Even where it did not hamper the bees' feet, the stale, sour smell of the stuff put them off their work; though some of the bees who had taken to egg-laying said it encouraged them to be mothers and maintain a vital interest in life.

When the caterpillars became moths, they made friends with the ever-increasing Oddities -- albinoes, mixed-Ieggers, single-eyed composites, faceless drones, half-queens and laying sisters; and the ever-dwindling band of the old stock worked themselves bald and fray-winged to feed their queer charges. Most of the Oddities would not, and many, on account of their malformations, could not, go through a day's field-work; but the Wax-moths, who were always busy on the brood-comb, found pleasant home occupations for them. `02

Kipling's tale turned out to be a prophetic one. In 1909 the world had had little intimation of the Marxist rule to come and relatively little of its souring philosophy. Yet the author could look through all of history for betrayal of the common weal. Fifth column would not develop until the Spanish Civil War, yet Trojan horse runs back to the time of Moses.

Kipling resolved the conflict in The Mother Hive by following nature's own procedure for saving bees -- having a Queen and a swarm of vigorous workers leave the diseased and dying hive. In so doing, however, he converted a political allegory into a moral and spiritual one. The allegory deals with the ruination of a culture, and finally with the conflict between Satan and the power of God. The author has his devoted worker, Melissa, block out a royal cell in the farthest and most corrupted corner of the hive. He has her obscure it with such foul rubbish that no creature will come near. He has her prevail upon the dying Queen to make one last effort to lay a worthy egg. He has Melissa's companion, Sacharissa -- the nursing worker-teach a few young workers the lost art of making royal jelly. And finally he converts this remnant into co-conspirators to nourish and protect the young Princess against the impending doom -- when the time will be right for swarming to new life beyond the hive. `03

The little grey Wax-moth, pressed close in a crack in the alighting-board, had waited this chance all day. She scuttled in like a ghost, and, knowing the senior bees would turn her out at once, dodged into the brood-frame, where youngsters who had not seen the winds blow or the flowers nod discussed life. Here she was safe for the young bees will tolerate any sort of stranger.

A hundred years ago the Anglican churches had a quality they have since lost, though they have striven greatly to recover it. They were, to borrow a phrase from the Consultation on Church Union (COCU), "truly catholic, truly evangelical, truly reformed," This quality was theirs because their church had, from the beginning, been structured in three parts. For some members this had been a scandal, but for others it was Anglicanism's glory. It reflected an understanding of a God who is Himself triune.

There was an inside joke that Episcopalians used to describe the three elements in their church -- "high and crazy, low and lazy, broad and hazy." This was not an inaccurate description, especially when applied to ceremonial practice. High Church was "crazy" in that it used a Catholic ceremony that, for Protestants, was meaningless mumbo-jumbo. Low Church ceremony, though severely formal, was also severely simple, hence, "lazy." The Broad Church was made up of people whose interests were more sociological than theological. Their worship, like their teaching, was confined to what they regarded as "relevant," but for high and low churchmen it seemed to be merely hazy.

Ceremonial aside, there are solid reasons why a church such as England's should have developed a tripartite way of understanding and worshiping God. For God, if not tripartite, is triune, and each member of the Godhead has His own way of revealing Himself and of being worshiped and understood. God the Father is transcendent, and His revelation is embodied chiefly in Holy Scripture. God the Son is incarnate, revealed chiefly in His Church, and in the memoirs she has written. God the Holy Spirit is immanent, and his revelation is in "holy feelings" or "holy thoughts." This is a faculty that, in Anglican use, has been regarded corporately as Holy Reason. Only the last of these sources of divine revelation belong to the "now." The first two belong to the "then."

One can see why such a church must be as diverse in her views as were the fabled blind men who chanced upon an elephant, and who could not agree whether the animal was leg- or trunk- or tusk-shaped. High churchmen have `04 held a high doctrine of the Church, which has seemed to require a subordinate position for the Bible. Low churchmen were conversely high on Bible and low on Church. Broad churchmen were low on both Church and Bible, and high on Holy Reason and on science-supported logic.

Events of the past generation have brought a virtual end to this spectrum, and a new one has come to take its place. At least, it seems to be new, although its components are still Bible, Church and Reason. The realignment has been brought about by the confusion of our time, and by the spiritual and moral weakness of the age. For many Christians the old absolutes of Church and Bible have failed altogether; they are said to show only God-as-He-seemed-to-be and the relativities of past revelation. Therefore, it is held, such authority can be set aside, with the confidence that God-as-He-is-and-shall-be can be linked with Holy Reason.

As a result, the glory of Anglicanism has faded. The church that was a "bridge church" because it was the only one in the West to have any real triunity, has lost that balance and come under the domination of one of its three component parties. It is now like a three legged stool that has decided there is economy in having one leg do the work of the other two.

In the process of moving from a religious to a sociological view of man, the Anglican spectrum has rotated ninety degrees. It is now on a horizontal, rather than a vertical, plane, taking the posture familiar to any political situation. Rather than "high" and "low," the orientation is now "right" and "left." High churchmen and low churchmen are bundled unexpectedly and uncomfortably into a right wing, which is so labeled because both are traditionalist, i.e. both are dependent upon the revelation that God has given man in the past. The left wing consists of what are called "liberals" because, like liberals in the secular sphere, they take a "liberating" view of man. The titles, of course, are meaningless excepting as they impute a dependence upon past or present revelation. Actually, the classic liberal was more like the conservative than like the liberal of today. He sought maximum freedom for the individual in society -- but such freedom as could be borne responsibly. He expected an accountability by the individual to an authority outside himself, and he suffered license neither in the individual nor the group.

The Liberal's Constitution for the Church

In the contemporary understanding, what is a liberal? How do we recognize a liberal by what he says or does? What is the liberal's idea of the Church and of its life? What is the liberal myth -- that is to say, what is the unwritten constitution that dominates liberal thought and that provides a scenario for liberal action? How does that scenario differ from the traditional concept of the Church and of her life and work?

Basically, the liberal believes in the goodness of man. He accepts the witness of Genesis 1 as to the goodness of creation, but he rejects the testimony of Genesis 2 and 3 as to the greatness of man's fall. He cannot take seriously the view that man is prone to sin, and that once he has fallen it is virtually impossible for him to recover either his innocency or his virtue.

A corollary of his acceptance of man's goodness is the liberal's belief that `05 evil is primarily the result or ignorance, rather than of sin. As a result, he is committed to the idea of progress -- and indeed of the perfectibility of human society. Because of his belief in progress, he regards the present generation as the wisest and best-informed in the history of the race. And because of this he regards himself as singularly free. He is under no obligation to protect the continuity of his own people's past, but rather must be open to the truth, from whatever tradition it may come. In addition, he must be open to new revelations of truth, such as may not have been vouchsafed to anyone in the past.

It is a particular teaching of liberals that institutions created for the benefit of individuals tend to hurt, rather than help, them. This is an accompaniment of the basic doctrine; if man is innately good, he needs no institutions to further his goodness. He need be governed by no customs or traditions, or by others' value-systems. These things can only hinder his self-development, making him a slave, rather than "the free man God wants him to be."

Hence it is the liberals' conviction that the Church should be used for the reform of society rather than for the sanctification of individuals. Instead of ministering grace to its members and helping them to overcome a sense of sin and alienation they should not now have, the Church's task is to carry God's love to the oppressed and to the alienated and deprived. More than that, the Church is called to be the central, holy force for the reordering of society. It has the task not only of bringing God's love to the oppressed, but of seeing to their liberation, so that they can find themselves to be fully men.

Needless to say, the new liberalism has led the Church into a stance it has rarely held before -- and that it has never held, apart from immediate and urgent causes. It is a stance of official, doctrinal worldliness. The Church -- or at least those who dominate it -- regards the here-and-now as more important than the eternal. It regards the redressing of wrongs as more important than the sufferance of evil. It regards the causes of dissatisfied minorities -- whoever they may be and regardless of the legitimacy of their claims -- as more important than obedience to God's Law and the shepherding of His flock.

In the years prior to 1970 Episcopalians had several opportunities of seeing the ruthlessness of the liberals who had come to dominate the policymaking of the Church. [I say 1970 because, for reasons to be explained later, that was the year when the liberals shelved their designs for change in the social and economic spheres and concentrated on change within the Church.] One was in the way the General Convention Special Program (GCSP) was set up to give funds to people and agencies who had no commitment to Jesus Christ. Another was in the way 815 (the staff headquarters in New York) and the Executive Council abused that program by giving funds to groups that were openly committed to violence and -- in a few instances -- to the overthrow of constitutional government. A third was the way in which the liberal authors of this and other programs behaved when caught in violation of the ground rules imposed upon them by Convention.

This last fact ought, in 1970, to have convinced fearful right-wingers that `06 815 was not an arm of the Comintern. The true communist does not behave as the liberals did on that occasion. He is not so stubborn as not to bend when the tide is running against him. His tactic, rather, will be to give in to pressure, to accept the setback, and to transfer his attention elsewhere until the time is right for a return to the earlier point of pressure.

The Liberal's Constitution for Himself

There is one way in which the liberal differs from the old communist warhorse. He is not so much concerned with purposes as he is with persons. By contrast, the communist cares nothing for persons; in him there is no bleeding heart. And, where the communist is utterly unconcerned about the consistency of his position, the liberal has a horror of flip-flops in the party line. For him, consistency is an absolute necessity if a posture of unchanging love is to be maintained. As a consequence, he has an intense concern for appearances -- what the Japanese call face. He not only fears the thought of saying or doing something that is not strictly in accord with party line. He is apprehensive over any association that may link him with reactionaries.

In this, the liberal is behaving like a member of any ethnic group. ("Ours are the good guys, theirs are the bad guys.") But he is supposed to be no such thing. The liberal's cultus has the intention of transcending every ethnic boundary. To belong to such a cult, the liberal has denied every instinct that has tied him to an ethnic past. He has tried to identify himself with ethnics from a different background than his own. Unfortunately, such people, for the most part, do not want to be identified with him. They are suspicious of turncoats, and so the liberal winds up outside both camps -- a camp follower, as it were. In self-defense he identifies with the only others who are like himself -- those who also put "personhood" above principles. In such company, however, he finds himself in a continuing identity crisis, for identity requires definition and he will not allow himself to be defined. Who is he? What does he believe in? No one can say for sure.

The tragedy of liberalism, as we see it today, is that it comes close -- but not close enough -- to the stance required for successful mission. It is true that the Christian witness cannot sit at home in the security of his beliefs. He has got to be open and involved to the point of putting every treasure behind him and risking all for Jesus Christ. But this openness has got to be for the sake of the kingdom, and not for the meeting of one's psychic and social needs. The true witness cannot risk over-involvement when his task is to point to One whose kingdom is not of this world.

Long before Dietrich Bonhoeffer called Him "the man for others," the liberal was proclaiming the universal humanism of Jesus Christ. Such a gospel, however, is a distortion that we have suffered all too long. It has driven millions of young church folk into a mysticism that has nothing to do either with Christ or the good.

With the sincerity of his position beyond doubting, the liberal can best serve today by focusing on Christ's divinity rather than on His humanity, and by allowing his own belief to be enlarged. When the liberal has received God as He has revealed Himself, and when he has accepted the benefits of Christ's sacrifice upon the Cross, "openness" and "involvement" will find their real meaning. `07

"Don't call me 'Miss.' I'm a sister to all in affliction -- just a working sister" . . . The Wax-moth caressed Melissa with her soft feelers and laid another egg.

"You mustn't lay here," cried Melissa. "You aren't a Queen."...

"Don't be unkind, Melissa," said a young bee, impressed by the chaste folds of the Wax-math's wing, which hid her ceaseless egg-dropping.

The seventh and eighth decades of our century have seen, more than any in our history, the blasting of our two most important institutions -- the family and the parish. In less than a generation, these prime bulwarks of society have been subject to such a shock that they have lost their power, their promise, and, to a large extent, their meaning.

Without getting into an explanation as to why this has happened, let a few case histories be witness to the fact. All of them are true, though with a few exceptions the names and places are disguised. They are told, not so much because they are scandalous as because they involve the kind of scandal that has never before happened in our world. It bespeaks a mentality that indicates people in the highest places have lost their wits -- and are leading their followers, lemming-like, into a terminal tide.

Priest Power

In the late 1950's the Reverend J. Worthington Gantry was called to be rector of St. Asaph's, Montmorency, a far suburb of Philadelphia. St. Asaph's was renowned as Cram's finest work, built at a time when Montmorency was the wealthiest and stateliest town in the country. By the fifties, however, the place had become down-at-heel. The great estates had been sold and converted into housing and industrial developments. The town houses had become rooming houses, providing shelter for a growing number of transients. The remnant of the once-proud families were haunted by the shabbiness they saw on every hand. The chief monument to Montmorency's past was the parish church itself -- and its two million dollar endowment, which would maintain the fabric against the inroads of time and decay.

Despite his new prestige, the incoming rector felt uneasy. St. Asaph's had for years been dominated by a few powerful men, whose connections with important people, both in the parish and in the church, enabled them to have their way. These men, who as wardens had been supported by an inside vestry, had succeeded in ousting two of the three previous rectors. As the new incumbent, the Reverend Mr. Gantry expressed the hope that the parish could be democratized, and that the principle of a rotating vestry could be adopted. `08

As it turned out, nothing could keep the old system going. In St. Asaph's, as elsewhere, the perpetual warden was a dying species. A leveling society no longer provided men and women who had the leisure, the wealth, the devotion or even the moral certainty to give a secular guarantee to the things of God. As a result, there was a transfer of power. Yet the effect was not salutary. The parish's control was not transferred from the few to the many; rather, it devolved from the few to the one. The fixed vestry was not supplanted by a rotating vestry. Rather, it was a whirling vestry, whose members were spun off and out of the system as rapidly as they gained an understanding of it. The dominance was gained by the rector, and the vestry became a rubber stamp.

The Meaningfulness of Christmas

Lancelot Lovelace's first assignment as curate was to stage the annual Christmas pageant, which packed the ancient church as no Prayer Book service had ever been able to do. Written in 1796 by the first rector, The Bethlehem Story had proved to be the most durable liturgy in the diocese. Its excess of traditionalism, however, had traditionally been offset by the sermonettes of St. Boniface's curates, who had by custom emceed the show.

Young Mr. Lovelace had broken tradition in one way by being the first curate to have a wife and children; his eight year old twins were the darlings of the parish. As it turned out, he was to break tradition in quite another way, using a modern translation in place of the time-honored King James' Bible. As parents and sundry relatives leaned back to hear the beloved line, "with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child," they heard instead, "He took with him Mary, his fiancee, who was obviously pregnant by that time."

The congregation's ruffled feelings were soothed when Mr. Lovelace recounted the story of Mary and Joseph and the Christ child. He did it with simplicity and charm, and concluded by pointing out that the important thing about the Bethlehem event is not what may actually have happened, but how one responds to it. To illustrate his point, he told how Lucy and Lisa had come to him the previous Christmas to ask what Christmas meant. His answer had been, "Girls, you shouldn't ask me what Christmas means. You should ask yourselves. You should ask, 'What does Christmas mean to me?'" At this the congregation sighed with relief. The curate was one of them after all.

One veteran Church School teacher, however, was not impressed. She was Lucy's and Lisa's own teacher. The next Sunday in class Mrs. Kyd asked the girls how they had reacted to their daddy's advice. Lucy turned to Lisa, thought for a moment, and then spoke for both, "We told daddy that we didn't know what Christmas meant. We wanted to know what it meant to him and everyone else."

The Ministry of Healing

In March of 1965 Dr. Alfred Price, the warden of the Order of Saint Luke the Physician, held a three day mission of spiritual healing in Morristown, `09 New Jersey. Hundreds of people flocked to the services, and nearly a hundred professional people -- doctors, nurses and clergy -- came to a lunch, where they could meet and hear the well-known Philadelphia rector.

At a question and answer session at the end of Dr. Price's talk, it became evident that several of the younger clergy regarded the idea of prayer for the sick and the laying on of hands as an aberration. "How can you waste your time dealing with sick individuals," one young priest asked Dr. Price, "when the world's sickness is crying out to be dealt with?"

Dr. Price endeavored to satisfy the young man's concerns, realizing they were shared by a number of his colleagues. He cited the New Testament to show how, for His hearers, Jesus' miracles were proof that His preaching and teaching were true. He showed how bodily healing was a fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy and a proof that the Kingdom of Heaven was at hand. He demonstrated from the Bible how a healing ministry is a mandate from Jesus Himself -- not only for clergy, but for lay people as well. Dr. Price's young hearers were not convinced. They remained firm in their belief that the healing of souls and bodies was a waste of time, if not an impossibility, and that the Church's real mission is to heal the sick structures of a capitalist and imperialist world.

The Holiness Fathers

Shortly after the Trial Rite was introduced in 1971, Thad Hemmings went to his first jazz mass. It was at Grace Church, Montgomery, and was put on by the Holiness Fathers, assisted by some sisters of the Order of St. Clementine.

At the time, Thad was a college sophomore, dedicated to campus rebellion and filled with outrage over racism, pollution, Vietnam and the military-industrial complex. While still on good terms with his parents, he sturdily refused to trim his hair -- on the grounds he would be betraying his generation.

Thad went to the jazz mass with some reservations. A week or so earlier he had been invited to a College Open House at the rectory of his own church to meet the famed university chaplain, Bertram Butt. The rector, beaming with pride, had introduced Father Butt as "one who has something to say to the youth of today." But as Thad soon found out, Butt had nothing to say. It was a fact that was only partly concealed behind the chaplain's discreet obscenity and his glib use of academic jargon. Thad asked some penetrating questions, trying to find Fr. Butt's loyalties and commitment. But there seemed to be none.

The jazz mass was something else. The brothers and sisters had staged an elaborate setting for the youngsters who were expected from all over Madison County. The church hall was filled with gas-filled balloons, crepe paper backdrops, great pyramids of colored cardboard cubes, and the mind-bending scream of electric guitars.

The next morning the young man met his father at breakfast. "How was the jazz mass?" he was asked, as the senior Hemmings put aside his paper. Thad paused a moment before giving his answer, "Dad, I hate to say this, but I'm afraid it's true. Those monks are deliberately trying to widen the generation gap." `10

A Terminal Case

Christopher Crowell ought to have known better. He was already, at 34, one of the cardinal rectors in the diocese, and his success up to this point had consisted, at least in part, in being the kind of priest people expected him to be. When he had been interviewed two years earlier by the St. Mark's calling committee, he had seemed like a rock of conservative dependability.

But now, secure in his post, he seemed ambitious to be something else. His sermons had changed; he was not speaking of Jesus Christ, but for the need of improvement in the secular world. His gospel of love consisted chiefly in making people feel uncomfortable for the sins of their kind. His new identification as a saved (or, rather, a liberated) person was not with those who looked up to him, but with his clerical compeers. As an "open, aware and sensitive person," he was drawn to the kind of priests who were to be found in the wealthier parishes and in the key diocesan committees. There were those who were saying that Christopher Crowell's chief aim was now to be bishop.

When the senior warden came to see young Crowell, however, the priest behaved like a lad who's been caught with his hand in grandmother's cookie jar. "Rector, I've been asked by several people to speak with you about a pastoral matter we feel you've mishandled."

"Oh?"

"We understand that when Mrs. Lydecker was dying she asked for you to bring her Holy Communion."

"Yes, she did. What about it?"

"It seems that when you arrived with the Sacrament you were wearing sneakers and tennis shorts."

"What's wrong with that?"

"Don't you see any absurdity in that? Or even any profanity?"

"No."

"Well, you're the only one I've talked to who doesn't, and I can tell you I've talked to quite a few. Most of the people who know about this feel it's an outrage."

"Jeff, I was playing tennis when they called me from the hospital, and I rushed over there as fast as I could."

"Your secretary says that Mrs. Lydecker sent word to you two days before."

"That doesn't matter, Jeff. The important thing is that what I was carrying was the Body and Blood of Christ. What I was wearing couldn't have affected the validity of the Sacrament."

"You could easily have slipped on a cassock over your tennis clothes. You had to go to the church to get your communion set."

"A cassock in Community Hospital -- with sneakers? Now that would be absurd."

"Rector, there's only one thing your parishioners are concerned about, and it has nothing to do with the way you looked. It has to do with the regard you have for your people. The nurse told one of the family that when `11 Mrs. Lydecker saw you she was so shocked that she couldn't receive, and that she died without making her communion. She said that instead of going back and changing your clothes, you gave Mrs. Lydecker the same argument you're giving me."

The rector began to expostulate, but was cut off with a wave of the warden's hand, "Here's how we feel about the matter. We feel you let a dying woman down. And in letting her down you have let everything else down -- your ministry, your congregation and the Lord, whose servant you are supposed to be."

Laypersons Plain and Fancy

The diocesan convention was an eye opener to the delegation from St. Agnes' Plainville. Excepting for the rector, none had even been to a convention before. To make matters worse, the three knew too little about the church to vote with any confidence or even to venture an opinion. They felt like country bumpkins in a big city -- awed by other people's assurance and embarrassed by their own inadequacy. Jim Petrovich was a retired Navy CPO who was now working as a security guard. Gertrude Pfaff was a widow with a precarious living and many mouths to feed. Nancy Brown was a retired schoolteacher who was terrified at the thought of speaking into a microphone. To make matters worse, the arrangements committee had separated the St. Agnes' deputation from its own archdeaconry of little churches and plain people, and seated it among the delegations of some of the wealthiest churches in the country.

It was an unfortunate mistake, for the convention was debating some of the most sweeping changes in order and worship that had ever been proposed, and the St. Agnes' people found themselves intimidated by those at the nearby tables. Every one of them seemed to be tall, handsome, fashionably attired and "involved" -- ready to sound off vigorously and articulately on whatever matter was at hand. In addition, they seemed all to be of one mind. When they voted, the twelve Jefferson county churches did so as a bloc. On a resolution for the priesting of women, for example, they stood as a body when the ayes were counted, and cheered when the tabulations were announced. They made plain their disapproval of the one resolution St. Agnes' offered -- that diocesan meetings be held on evenings or weekends so that working people could be active members of the various commissions.

As the delegation was returning home, Jim Petrovich turned to the rector and said, "Gosh, Father Bill, I felt like a fish out of water! You know me, I usually get up on my feet and air my views, but with that gang looking down our throats I didn't have the nerve to open my mouth."

Before the rector could reply, Gertrude Pfaff spoke up from the back seat, "Did you notice that woman at the next table -- the one who was chain smoking and who had her hair swept back into a bun? All day long she kept looking over at us like she wanted to spit on us, and when I stood up to vote against women's ordination I thought she'd rush over and tear my eyes out."

The rector half turned about so as to be heard in the back. "You've got to realize that these people are the affluent Americans. They're bright and well `12 educated and accustomed to getting their way. And they think they know what's best for the rest of us. If we don't agree with them they don't think of it as simple disagreement. As they see it, we have to be sick. If they're just plain rich they think of us as only entitled to half a vote. If they're young and liberal as well, they regard us as racist, sexist, reactionary chauvinists. You name it and that's what we are to them,"

Miss Brown, who had been silent all day, now chimed in. "When I was young we used to be a simple two-class society, and most of us were happy that way. My family was poor, but we had nothing against the affluent because that was what, some day, we wanted to be ourselves. Now we're supposed to be a classless society and yet there are more classes than you can count -- each depriving another one of its 'rights.' What nonsense! I'm supposed to feel guilty because I'm white, and I'm supposed to feel cheated because I'm a woman and old and poor. Well, I don't feel that way at all." `13

The Wax-moth crept forth, and caressed Melissa again.

"I see, " she murmured, "that at heart you are one of Us. "

"I work with the Hive," Melissa answered briefly.

"It's the same thing. We and the Hive are one."

"Then why are your feelers different from ours?"

It takes some time for a sound bee to realize a malignant and continuous lie. "She's very sweet and feathery," was all that Melissa thought, "but her talk sounds like ivy honey tastes."

The spring of 1970 saw the gravest domestic crisis the U.S. had known since the Civil War. A decade of tension over Vietnam and several years of racial violence in the cities had been followed by a series of bombings and killings that caused jitters throughout the land. The impending trial of Black Panther Bobby Seale, the courtroom murders in San Rafael, the blasting of the Wisconsin research center as a protest against the "military-industrial complex," random bombings by Weathermen and other student radicals -- all left the American public in a state of shock. When, to these, there was added the student outrage over Cambodia and the killings at Kent State, the stock market took its worst plunge in forty years. It was on the ninth of May that a sleepless President -- after making fifty telephone calls between 10:30 p.m. and 4:30 a.m. -- drove out to the Lincoln Memorial for a pre-dawn conversation with students there on vigil.

On the 22nd of the same month, the Executive Council of the Episcopal Church reacted in the same panicky way. In a resolution approved that day, the Council, acting in the church's name: 1) demanded an immediate withdrawal of all U.S. armed forces from Southeast Asia, 2) demanded a drastic reduction of strategic forces elsewhere in the world, 3) protested the government's harassment of Black Panthers and use of National Guard and police in killing students, 4) expressed support of striking and rioting students, and 5) called for a voluntary church offering to finance future strikes and to enable students to engage in "political education campaigns" directed at their elders.

As a result of this Council resolution, several hundred parish vestries wrote or wired their censure. This sign of spontaneous and widespread dissatisfaction with the church's leadership, had little effect on decisions at the top. It took direct action from Washington to change the church's mind.

On September first a postcard was sent to all clergy by the Presiding Bishop, the Rt. Rev. John E. Hines, "Plans for a proposed offering on the 3rd Sunday in September 'for the support of student strike activities, including their political education campaigns, have been suspended pending further action by the Executive Council at its meeting in October. . . The Internal Revenue Service has advised that implementation of the offering will jeopardize `14 the tax-exempt status of the Domestic and foreign Missionary Society."

It is an ironic fact that the concerns of churchmen -- expressed for so long and in so many ways -- should for years have been ignored by their leaders, while one threatening letter from the I.R.S. should bring their whole program to a screeching, grinding halt. Yet that is what happened. At its very next meeting the Executive Council rescinded the controversial resolution.

Yet the liberal spirit would not be quenched. After all, the liberals were still in the seats of power, and were less likely to be put out of office than would have been the case were they the chosen leaders of the State. Deprived of their ability to work for the radical change of society, they began to labor for the radical change of the Church. From 1970 on their social programs became a side issue, and they concentrated upon things the State could hardly object to, such as Prayer Book change and ordination of women to the sacred priesthood. It was only after they achieved some assurances of success in this direction that they began once more to broach matters that must concern the state, such as the civil rights of homosexuals and the right, for women, of abortion-upon-demand.

La Dolce Vita, Clergy Style

It was the summer of '75. Two priests were having lunch together, and their talk turned to the state of the church. Here is a fragment of their conversation:

"Bob, if you think sensitivity training is undermining authority, think what it may be doing to morality and behavior. Do you remember Gus Briggs? He was a year ahead of me at seminary. Well, Gus was a priest in Milwaukee until a couple of years ago. He had a wife and three children, and seemed as happily married as any of us. Then he went out to California for a three week seminar at the Esalen Institute."

"What happened?"

"Well, it's hard for me to believe this myself, knowing them both. But the minute he got home he said, 'I want a divorce.'"

"Wow! How did his wife take it? What did she say?"

"She was crushed. And when she asked why he wanted a divorce, he said, 'I've decided that marriage is just not my life style.'"

The conversation continued in the same vein, dealing with the demoralization of the times and the seeming inability of the Church to speak with firmness or authority. At length the host said, "Here's an example of what I mean. Did you know that here, in this diocese, there are four priests -- all separated from their wives and living openly with other women -- who are working regularly as supply priests?"

"You've got to be kidding!"

"I am not. I'm serious. There are four men here who were rectors in big churches, who had to resign because they were having affairs and their congregations found out about it. But outside their parishes it seems they are still considered fit. The people in the churches where they supply don't know, of course, about their way of living, and the bishop seems willing to allow it -- on the grounds that what people don't know won't hurt them." `15

"Haven't any of the clergy complained about this?"

"Only one that I know of."

Cardinal Layman

Francis Etheridge has more than once been called "the lay pope of the diocese." Though still in his middle forties, he has been his parish's representative to diocesan convention for nearly twenty years. For nearly ten years he has been his diocese' deputy to General Convention as well. Seattle, South Bend, Houston, Louisville -- all are a part of his background, and in them he has left his mark upon the Church as well.

Today Francis Etheridge has more clout than any priest in the diocese, and is more influential in decision-making than anyone excepting the bishop. Over the years he has been chairman or member of nearly every important commission in the diocese, and is a fixture on the Diocesan Council. He is the envy of the clergy for his freedom from the cares and burdens they must bear, and for his intimacy and familiarity with the bishops.

This does not mean that Etheridge has the warmth or the wisdom and wit to make him a lay prince of the church. He does not, but rather is unimaginative, impersonal and deadly serious. His qualifications for being a pillar of the church are the background things: family, schooling, wealth, looks and demeanor. More importantly, Etheridge is a born bureaucrat. His years in the law have developed an aptness for double-talk, and his contacts with the clergy have further salted his speech with ecclesiastical jargon. Using such terms as thrust, involvement, participatory democracy, I hear you saying, I move you, he can anesthetize the minds of all but the wariest listener.

Only in recent years have the people of Holy Innocents' begun to sense the harm their support of Francis Etheridge has done both to themselves and to the Church. Originally, his preference for diocesan affairs seemed an idle whim. Most of the real workers in the parish were dedicated to the parish itself, and it was felt that delegates to convention should be the fringe types -- the young and available, the rector-worshipers, or the kind who were active in the League of Women Voters.

Yet, as Holy Innocents' became increasingly alert to the goings-on in the church, its people became aware of the desperate need for convention deputies who would represent their people's minds. With mounting alarm they learned of manipulations, scandals and infidelities on high -- both in the diocese and in the national church. What bothered them most was the knowledge that their elected representatives were dedicating their holy offerings, not to relieving the poor, but to overthrowing the whole social order. This was true not just of those they read about, but of Francis Etheridge as well. It was said of him that at an elegant dinner at Sally Vanderbilt's he had spoken up, as the guests were seated, with the words, "Silence, please." Thinking he might be about to say grace, they had dutifully lowered their heads -- whereupon Francis Etheridge lifted his wine glass and loudly proclaimed, "To black power!"

It was not until the Philadelphia affair in July, '74, however, that Holy Innocents' learned what it was really like to be betrayed. The congregation `16 had taken years to learn of Etheridge's contempt for them, and now they found the extent of his infidelity to the church. At that time he presented the parish's curate, Samantha Smull, for "ordination to the priesthood." In behalf of an unknowing congregation and an unwilling diocesan, he certified her to three unfaithful bishops.

The events of the year that followed were more of unholy confusion than of holy order, but they led to one resolve on the part of the people of Holy Innocents' -- that Francis Etheridge should no more represent them. When, at the annual meeting, his name appeared as a candidate both for vestry and diocesan convention, the voters had their revenge. Etheridge ran last on both counts.

However, the mills of the electoral gods grind slowly. Francis Etheridge had been thoroughly repudiated at home, but his infidelities were as yet unknown to people beyond the parish. Sure enough, when the time came 'round for diocesan convention, Etheridge's absence was scarcely noted. Few of the delegates knew that he had been Samantha Smull's presenter. Even fewer knew how his congregation felt. He was still a "lay pope" by the possession of a name that had not been besmirched beyond the boundaries of his parish. He still carried weight in the church because some people found him useful despite his infidelity, and because others were too timid to accuse him, and because the great majority either did not know or did not care. In short, he was overwhelmingly reelected as a deputy to the forthcoming General Convention.

The Hijacking of the U.T.O. (United Thank Offering)

During the years that General Convention had been involved with the extension of the Gospel, it had been a task of the Women's Auxiliary to engage in works of charity. The men who were deputies to Convention had provided for missions at home and abroad, for seminaries, and for all the time-honored ways of winning the world to Jesus Christ. The women, at their triennial meetings, had given to the work that was a secular accompaniment of missions -- like hospitals and clinics -- and had established agencies ranging from the care of the poor and needy to the rehabilitation of criminals, alcoholics, the blind and dumb, as well as unwed mothers. The concern might, in today's jargon, have been called "total involvement." It was accepted, however, that the Church would not engage in some new task until everyone was agreed.

By the middle sixties Walter Rauschenbusch's Social Gospel had given an entirely new twist to the meaning of involvement. His message had penetrated the church sufficiently to give plausibility to the idea that helping the poor meant helping them to get their rights. It had won credence for the belief that giving to the poor meant not only "giving what is ours," but "giving what is someone else's," and "giving that which rightfully belongs to the poor." The social Gospel's apparatus, which included bureaucracies, programs, pressures, promotion and manipulation, had acquired enough of a vested interest for its edicts to be issued from on high.

When the Episcopal Churchwomen's delegates went to Seattle in 1967, `17 they found that the hierarchy had taken over entirely, and that the only prerequisite to participation was a mind uncluttered by commitment -- a tabula rasa, as it were. They were told that the Church was changing its priorities, and that the new concern was a "total" one -- the urban crisis in America.

During the first four days of the triennial the delegates had no opportunity to hold either committee or plenary meetings. Instead, each diocesan delegation was brought together with those of two other dioceses, and required to engage in small-group discussion of three questions only:

1) What do we understand the Urban Crisis to be?

2) What should the response of this Triennial Meeting be to the Urban Crisis?

3) Can we examine the consequences of action we propose to take here to our own parish or diocese?

Understandably, the delegates were frustrated. They had expected parliamentary procedures, and were shunted into the simpleton structures of the buzz session. They had expected the customary division of labor among specialized committees. Instead, they got the T-group, whose leader forbids the development of agenda until "confrontation" assures which way the group is going.

As a result, the churchwomen devoted a large part of the United Thank Offering to the Urban Crisis Fund. Four days of sensitivity training had exhausted their psychic and moral defenses, and had left them with concern only for one another. Gone was the sense of representing the interests of the women back home. Gone was the commitment those women had made to the hundreds of projects and thousands of people for whom their churches had held a sheltering concern. They had surrendered the legislative process entirely. They had become a rubber stamp instead of a determinative body. For the first time the women had given their offering to the hierarchy, leaving the U.T.O. with no reserve to meet emergencies during the three years that lay ahead.

The Campus "Square"

For eight of his ten years as Episcopal chaplain, Jim Alexander had been chosen by seniors as one of the most popular figures on the Winchester State campus. And for eight of those years he was supported by the Church in the performance of his job. A big, outgoing man, Father Alexander was the older-brother type. He projected the values and virtues that youngsters longed to see and that parents wished they had. Even though a young man, his experience was broad and his commitment deep; he was able to preach Christ by example rather than dictum. His personal philosophy was the homespun type. He was concerned with God and country, with the needs of society as well as of individuals, with sound manners and self-respect. His simplicity of life and purity of expression told his charges all they needed to know about the meaning of inner discipline and restraint. `18

It was not in his relations with students, but with the diocese, that Father Alexander's problems were to come. In the late sixties, as students' hair grew long and their fuses short, there were those in high places who were concerned over the chaplain's lack of "involvement," over his seeming inability to change with the times, and above all over his unwillingness to adopt the goals of campus revolutionaries.

Actually, in the years when student protest was the angriest, Winchester State was one of the least involved of the great universities. The chaplain's proteges were the straightest of the straight. They included campus athletes, beauty queens and every intellectual type. On the chapel's board of student governors were six of the eight junior Phi Beta Kappas; only one was an Episcopalian.

If the university was conservative, the state was even more so. The liberal Establishment had never gotten a footing in the commonwealth, and was only beginning to do so through the Church. The principal change-agent was the Episcopal bishop, Benjamin Arnold, whose election in 1960 meant one thing: the controlling clique at church headquarters was determined to radicalize the Diocese of Penrhyn, and to use its endowments to support their programs elsewhere. In his earliest years as diocesan, Bishop Arnold had gotten himself the staff he wanted and had used his power as rector of the diocesan missions to install a number of young revolutionaries as vicars. In addition, he had arranged for the choice of several outstanding liberal clergy as cardinal rectors in the diocese. By 1970, when the campus' rebellion was at fever heat, the bishop was ready to use his weight in the affairs of Winchester State.

Father Alexander's first run-in with the bishop came when the latter asked him to become involved in the defense of the Students for a Democratic Society, at a time when the S.D.S. was under fire for its connection with the Weathermen and for its own violence directed toward companies with Defense Department contracts. The chaplain refused; he would have nothing to do with S.D.S. and would not engage in the smokescreen tactics the bishop was suggesting. The bishop then joined forces with the Methodist chaplain, who had been an S.D.S. supporter all along, and they worked together until their joint repudiation led to the bishop's resignation and subsequent appointment to a more strategic post in New York.

The new bishop, Gaylord Wimpel, went even further than had his predecessor; one of his first acts was to appoint a committee for chaplaincies, whose task was to make a yearly evaluation of the role and the work of the various chaplains, and to recommend budgets for their work. As a result, Father Alexander found his budget cut substantially. His relations with the diocese were further strained when he was drawn into another matter: an investigation into the management of the diocesan camp. For several years, it had developed, young people at the camp had been permitted, with only mild disapproval, to use drugs, and were now being given sensitivity training while in a freaked-out condition. The chaplain's part in the matter lay in his demand for an investigation into the death of one of his girl students, who after one of these sessions and the use of drugs, had tried to fly from a cliff, and had fallen to her death. `19

It was not long before Father Alexander's own ministry was under investigation. At the demand of a student radical, an appointee of the bishop's to the Diocesan Council, full scale hearings on the Winchester State chaplaincy were undertaken. The bishop's committee interviewed a number of students who testified to the "irrelevancy" of Father Alexander's ministry. (All of them, the chaplain later told a friend, were addicted to drugs.) His accusers were joined by two faculty members, who later became the local vanguard of "gay liberation."

A difficulty faced by the chaplain was the failure of the committee to have a quorum when his own witnesses were scheduled to appear. Repeatedly he found himself unable to be represented by anyone other than himself. The final sitting, however, brought together the entire committee and all of those whose testimony the chaplain sought to present. In addition to the bishop's appointees, there sat with the committee -- ex officio -- the Church's Executive Secretary for Higher Education, the Rev. Phanuel Thugg, and his lay assistant, Dr. Washington Bridge.

In their informal introductions prior to the meeting, Fr. Thugg behaved with a candor remarkable to one in his position. When introduced to the president of the student body, he made a wry face and said, "Big deal." In meeting Bill Grove, the famed halfback (now a star player for the Miami Dolphins), he ignored the young man's outstretched hand and squatted on the floor like a chimpanzee, arms akimbo and digging his fingers into his sides, "Yip, yip, yip, yip, the All-American boy!"

Most stunning was Fr. Thugg's assessment of Andrea Somerfield, while the coed was entering the room. Miss. Somerfield was a lovely blonde girl who had been homecoming queen and who was vice president of the chapel committee. Before any introduction could be made, Fr. Thugg remarked in a loud voice, "Oh ho, the campus virgin." Then, as the girl stared at him, blushing furiously, he dug his elbow into Dr. Bridge's ribs, "Two to one she'll graduate from this place without ever being f---d."

The executive secretary proved to be the investigation's undoing. Even a determined committee was unable to hound the chaplain further in the face of Thugg's behavior. Soon after its findings were returned, however, Father Alexander resigned his chaplaincy, accepting a post at the university as assistant professor of speech and drama. He is still there, exercising his priesthood in a very minor way. His replacement, as might be guessed, turned out to be a radical priest -- anti-U.S., anti-capitalist and anti-college administration. The church had finally gotten a chaplain at Winchester State who was "open" and "involved." `20

V. THE UNDOING OF THE SEMINARIES

The Oddities . . . would sing of work among the merry, merry blossoms till an untrained ear might have received it for the hum of a working hive. Yet, in truth, their store-honey had been eaten long ago. They lived from day to day on the efforts of a few sound bees, while the Wax-moth fretted and consumed their already ruined wax. But the sound bees never mentioned these matters. They knew, if they did, the Oddities would hold a meeting and ball them to death.

Nowhere is the vaunted freedom of the Anglican Church more manifest than in her seminaries; they range from catholic to unitarian, from secular to ascetic, from "liberated" to carefully governed. In this respect they are true of the Church, for her main hallmark -- freedom -- is what lies behind her tolerance, her inclusiveness and, above all, her success in producing people of imagination, enterprise and achievement.

It may be supposed that this freedom is what has brought our difficulties upon us, yet this seems not to be the case. We find proof in the experience of two of our sister churches where freedom has been almost nonexistent -- the Roman Catholic and the Missouri Synod Lutheran. The Romans have had tight discipline from beginning to end. They have sought vocations to priesthood at an age when Anglicans would be urging reluctant lads to confirmation. They have enforced a rigorous control over both clergy and laity, not only as youngsters, but through the whole of their lives. Yet their church is gravely shaken by liberalism because their leaders were never exposed, as youths, to the hazardous possibilities of broad-gauged thought and action. By contrast, the Lutherans have given their clergy and congregations a great deal of freedom, once they were mature. But even this polity has come a cropper with the invasion of the seminaries by a few determined and self-seeking men.

Our Anglican difficulties are, it would appear, brought on by three factors that are in force everywhere, and nowhere more so than in the U.S.A. One is the rise of liberalism to the point where it is no longer an authentic element in a delicately balanced church, but the controlling force in a nearly totalitarian situation. A second factor is the timidity and insecurity that leads those with the highest responsibilities to be the first to compromise. A third is the egomania that leaves it up to man to decide what is right and wrong.

Touching the seminaries, there are three popular notions that seem to be `21 at the heart of much that troubles the church. One is the notion that the ministry should be open to those who desire it, rather than to those who -- even against their wills -- are genuinely called by God. Another is the notion that the hallmark of the Christian is not self-denial, but self-affirmation. The third is that the primary function of seminaries is to educate, rather than to train, the priest.

Nowhere in the church's recent literature is this platform more clearly implied than in the 1967 Pusey Report [Ministry for Tomorrow, Report of the Special Committee on Theological Education (New York, Seabury Press, 1967).], whose authors proposed a set of new roles to replace "archaic" forms of traditional ministry. Today, only nine years later, the idea of new roles has been scrapped, and liberals are using every effort to force into the old forms those who, in the past, were not admissible. The liberal platform, however, remains intact. The ministry is an elite corps -- open to anyone who wants to try. It is Christian to do one's thing, and old hat to be restrained by conscience. The priest is a professional, and entitled to the same considerations and courtesies as the lawyer or the doctor. In all this there is not a shred of the humility and the sense of vocation that is expressed in St. Paul's first letter to the Corinthians:

You see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called . . . but God hath chosen the weak . . . that no flesh should glory in his presence.

A Bill of Particulars

Not long ago two clergy met for lunch in a small restaurant in New York. Seminary classmates at Exmouth, they had not seen each other since their ordination eighteen years earlier, and as it developed they had far more in common in 1975 than they had seemed to have in 1957. At that time the younger, Ralph Waiters, had been an evangelical low churchman, and openly critical of the "spikey-ness" of Exmouth's brand of religion. Walters had been the top man in his class, and had had strongly in mind the possibility of teaching in seminary -- but another seminary, not Exmouth. By contrast, Bliss Cunningham's was a late vocation. Already in his mid-forties, Cunningham had had a successful career in advertising, and was one of many whom the Lord seemed to be sending to fill the ministry at a time of clergy shortage. Unlike his fellow priest, Cunningham had come to seminary a convinced catholic -- dedicated to the seven sacraments and to the authority of Holy Mother Church.

It did not take long for the two to settle down on the reason for their meeting. Walters was hostile to the seminary's proposal to discontinue Greek and Hebrew from its curriculum, and was trying to build alumni pressure for their continuance. "Bliss," he said, "you came to Exmouth under the old man's canon, didn't you?"

"Well, in a way. I was only there a year, but I took all the canonical `22 courses for the middle and senior classes."

"How is it that you took New Testament Greek?"

"Well, you may remember that old Dr. Yerkes tutored me for three years while I was still in the advertising business. When Bishop Bostwick accepted me as a postulant, he told Dr. Yerkes that he would dispense me in Greek, and R.K.Y. said, 'In that case, I will not accept him as a pupil.'"

"Ho, ho! And how did he put that over?"

"He said to the bishop, 'I regard Greek not as dispensable, but as the one indispensable subject. How can you ordain a man to be an interpreter of a book he can't even read?'"

"That's putting it on the line. But how did that set with you?"

"What kind of answer can you make to logic like that? I studied the Greek so hard that when I got to Exmouth I had a bigger vocabulary than anyone in the middle class."

"Oh, I wish to God that we had that kind of commitment today. You know, Greek and Hebrew have been optional for the last twelve years, but it's more than five years since anyone has elected Hebrew, And now they want to close the department and end the option on the ground that the biblical languages are an irrelevant frivolity in today's world."

Walters' face reflected his disgust as he ground out his cigarette, The two sat moodily for a few moments.

At length Cunningham spoke. "Ralph, you know more about the seminaries than anyone I know, and I was there such a short time -- and took such a heavy load of courses -- that I never got the feel of the institution itself. What do you see as the problem we have with the seminaries, and what kind of answers do you think can be worked out?"

"Well, Bliss, as I see it the problem extends in every direction. Perhaps it begins in the seminaries' independence. They have to raise their own funds, so they can't be altogether accountable to the Church. And because they must be solvent to survive, they are more concerned with their students as tuition-payers than they are as potential priests. During the Vietnam war they took a lot of draft dodgers just to pad out their rolls -- so now we have a lot of priests whose calling is dubious, to say the least. In the past few years they've taken large numbers of girls for the same reason, and the result is an artificially built-up demand to ordain women to the priesthood. The cult of permissiveness has turned the seminaries from screening out the latent homosexuals to screening in the active ones, and just as with the C.O.'s and the girl graduates, we now have an interest group with theological degrees -- and a built-in 'right' to be ordained."

"What you're saying is that instead of new ministries being determined by the church, they're being determined by the seminaries -- and for all of the wrong reasons."

"That's right, and there are two other things that I find disturbing. One is the permissiveness that allows a seminarian to take whatever courses he wants to, and that requires him to go to chapel only when he feels like it. The other is the curriculum itself. It's unbelievable how secular the seminaries have become."

"Ralph, if you remember, Exmouth was a pretty worldly place when you `23 and I were there."

"Bliss, believe me, it's nothing like it is now. I got a catalogue from Exmouth just a week ago, and I looked over it very carefully to see how it compared with the canonical studies that were required of every candidate for holy orders up until 1970. And you may not believe this, but it's true. Exmouth is now offering courses on psycho-drama, on protest, on aggression and survival, economic justice, guerrilla theater, psychotherapy, social change. But it offers almost nothing on the Christian religion as you and I were taught it. There's not a single comprehensive course on the history of the Western Church, and nothing at all on Eastern Orthodoxy. There's only one course on the history of mission, and none on overseas missions today. There's nothing on the doctrine of grace, nothing on the sacraments, nothing on the spiritual life. You can take more than a dozen courses on black theology and black sociology, but nothing on mystical experience. There are plenty of courses on such institutions as the family, the city, and the "Establishment." But there's nothing on the institution Our Lord founded. You can take more than two dozen courses on counseling, but none on prayer. It's hard for me to guess what the faculty at Exmouth are trying to do, but there's one thing I'm sure they're trying not to do -- turn out priests who are holy men of God."

The Post-Prayer Book Generation

During the summer of 1975, Fr. George Manners spent two months in an inner city St. Louis parish, freeing a seminary classmate for a much-needed vacation with his wife. The parish, St. Petroc's, is in a decaying neighborhood now occupied chiefly by Hispanic peoples. One of each Sunday's two masses is said in Spanish, using the Book of Common Prayer.

In late August, at a Spanish celebration, Fr. Manners noticed a neatly dressed young man among the communicants. At the service's close he learned the young man was a senior at the Episcopal Seminary of New Mexico. Catching him at the door, he invited the lad to breakfast, and his invitation was eagerly accepted, The two found much to talk about.

Fr. Manners declares that the following conversation is true:

Seminarian: Tell me, father, were you using the Book of Common Prayer? Priest: Yes, I was. It's a translation of the 1928 Prayer Book. Why do you ask?

Seminarian: Oh, I just wondered. I've never seen it before.

Priest: That surprises me. You've been in seminary two years, and you've never seen the Prayer Book in a Spanish translation before?

Seminarian: No, no. I've never seen the Prayer Book. I've never seen a copy in English or Spanish.

Priest: Good heavens. What kind of service books do you use?

Seminarian: We've used the Green Book and the Zebra Book, and we've used the Services for Trial Usage once or twice. But I don't even know if they have Prayer Books at the seminary. `24

Priest: That's amazing. You're to be ordained in less than a year?

Seminarian: I hope so.

Priest. And they expect you to promise conformity to the doctrine and discipline and worship of a Church whose Prayer Book you've never even seen?

Seminarian: I'm afraid that's right, father.

Eucharistic Blackball

It was the late spring of 1967. The place was Ridgeleigh, the antebellum mansion of the Grosvenors, now converted into a retreat house for the southern dioceses. It was the penultimate day of a month-long session for the sensitivity training of several dozen clergy.

The door slammed shut in bunkroom D as the last of the Nassau contingent trooped out on their way to breakfast. They had been slow in saying Morning Prayer, and the dining room was already emptying as they settled down at the only still-set table.

"I hope you don't mind my grumbling," said the Baytown rector. '"I'm planning a Post Meeting Reaction that'll dismember this whole operation."

As the others turned their heads, he added, "Oh, I don't mean this place. For this kind of thing, Ridgeleigh is as good as any other. What I object to is the kind of training where we make the Group take the place of God. They've deliberately allowed no chapel here. There's no holy place, no schedule for the daily offices, no time for meditation or prayer, no Bible study. And the Eucharist is always held after a meal so that it's virtually impossible for one to make one's communion fasting. And yes," he added, "there's this weird compulsion that everyone make his communion -- under pain of the group's displeasure."

The Nassau clergy were well into breakfast, their mouths too full to respond, so the Baytown rector continued. "Yesterday when Will Archer was celebrating, I came in after the confession. And since I hadn't made my peace with God, I felt silly when everyone jumped up at the Peace to offer me theirs gratuitously. I felt even sillier when the elements were passed around. How can you not communicate when somebody turns to you, and then puts the elements in your hands to give to someone else? Anyway, I didn't receive. Jim Long twice tried to feed me and seemed baffled that I wasn't joining in."

"You mean you were so ungracious as to turn down the gift of Christ?" It was the curate from Glen Cove, whose voice showed a touch of irony.

"No, dammit, it's not a matter of being ungracious. It's a matter of being unready, and of the individual making his own peace with God. I object to this arrangement where the group takes over and says, 'Baytown, you're all right with God the way you are.'"

The rector from Baytown's complaint was interrupted by the entry of the Nassau delegation's last and youngest member, who sidled into his chair with his tray still in his hands. Howard Trelawney was the newest curate at the cathedral. Because he was too young to be considered ambitious, he was doted on by the others. `25

"You won't believe what I have to tell you," stated Trelawney. "You knew, didn't you, that the East Virginia clergy were supposed to celebrate the Holy Communion this morning? Well, none of the six could agree on how to do it or on who was to do what. So they announced there would be no celebration, and when people seemed disappointed I said Nassau would do it for them."

"I don't believe it," said the Baytown rector. "How could anyone disagree on a thing like that to the point of backing down on an obligation?"

"They can, and did," said Fr. Trelawney.

"I can very well believe it," said the curate from Glen Cove. "Those people are all graduates of Old South Seminary, and they have absolutized meaningfulness to the point where if everyone doesn't do it his own way it isn't the Lord's Body and Blood."

"You have a point there," conceded the Baytown rector.

"But I do have a question," asked the priest from Glen Cove. "I think I know what goes on inside the Old South heads, and I'd guess that if they can't agree on how to do the Eucharist they would resent anyone else's offering to do it for them. How did they react when you volunteered our services?"

The eager beaver smiled. "They hated it, and when everyone else said 'Fine, let Nassau do it,' they held a little caucus and decided to blackball our celebration. So now everyone is going to be at the Holy Communion excepting the delegation from East Virginia."

The Dogmatics of Change

It was Theological Education Sunday, and a senior from one of the seminaries had been guest preacher at St. Swithun's in the Swamp. Afterward, in a small gathering at the rectory, he was asked some searching questions about women's ordination and about the discipline in the seminaries. "I happen to be in favor of ordaining women," he said, "just as most of my generation are. But I am mistrustful of most of the reasons for change, and I am mistrustful of those who take advantage of popular sentiment and ecclesiastical weakness to promote their ideologies."

Becoming aware of the attention he was getting, the young man threw caution to the winds, and got down to specifics on the things that were bothering him. "I wonder," he asked, "how many people who are in sympathy with the idea of women's ordination would still cast their vote for it if they realized that it is just one step in a timetable of cold and deliberate change. I wonder how they'd feel if they realized that it is not they who decide these things, but a small and powerful group who work behind the scenes, and who decide what the steps in the timetable will be. Black power -- that was last year. Women's ordination. That's on the agenda right now. Next year it'll be gay liberation -- with a few sidelines like polygamy, polyandry, legalized incest. But the main thing right now is homosexuality. You may not know it, but a lot of diocesan commissions have already passed resolutions commending the civil rights of homosexuals. A number have `26 approved the right of practicing homosexuals to be priests. And some of them are working on the right of homosexuals to be married in the Church."

As his hearers' jaws sagged in astonishment, the seminarian added, "These things were long ago decided in the seminaries. The new morality is a fait accompli. We have several sets of homosexual lovers living together in my dormitory. We have a priestess-professor who's called 'Lucy the Lesbian' behind her back. Another of our professors has his mistress living with him in his seminary apartment. And the top man on our faculty brags that he hasn't been inside a church for the past ten years." `27

"Now you see what we have done," said the Wax-moths. "We have created a New Material, a New Convention, a New Type, as we said we would."

"And new possibilities for us," said the laying sisters gratefully.

"You have given us a new life's work, vital and paramount."

"More than that," chanted the Oddities in the sunshine; "You have created a new heaven and a new earth."

From the early 1950's on, thousands of clergy and key laypeople in the Episcopal Church were exposed to the mind-bending techniques of Group Dynamics. The process, which was first financed with a $4 million grant from the Ford Foundation, took a variety of forms, including the Parish Life Conference, the Group Life Laboratory, and the many kinds of Sensitivity Training.

As a result of their indoctrination, a large number of the clergy adopted the social character that sensitivity training imposes. They became more "aware," more "involved," more "sincere," more "sensitive to the feelings of others," and their minds, in a shift of gears, became attuned to the situational rather than to the universal. As a result, many clergy were led to see their faith in terms of the humanitarian rather than the divine. Being so transformed, they dropped their old low-church or high-church affiliations, and switched to the liberal, broad-church party.

What was true of these clergy was also true of most of the laity who had undergone this training. There had not been enough money to indoctrinate more than the key laity, but at least their presence in the body politic gave the assurance of control by the liberal wing of the church.

The majority of the church's members, however, remained untouched by the new ideology. As with the lay people of other Christian bodies, they remained more steeped in tradition than the onrushing world about them. Thus, the end result of the group dynamics program was to widen the gap between the lay and the clerical mind. Its chief effect was to clericalize the church.

By the mid-seventies the well had run dry. There was no longer money for sensitivity training, and because of lay people's increased suspicions over church politics, there was less demand. In the fall of 1974, a weekend conference sponsored by Trinity Church, New York, had to be canceled for lack of applications. Its title had been, "Changing the Church deliberately: How to be an effective Christian change agent in the institutional church."

Despite this seeming lack of interest in sensitivity training by the laity, `28 however, the program's goals have been achieved: the Episcopal Church has been converted from a tradition-minded, multi-party body to a nearly monochrome, all-liberal church. As early as 1967 the man who had been the church's Director of Training -- and who had engineered the original Ford Foundation grant -- felt free to resign his post, with the idea of going to work for the radical labor-organizer-turned-community-sensitizer, Saul Alinsky. When asked by a friend why he was leaving, he replied, "Because we have finished our task. We have changed the thinking of the Episcopal Church."

The Unlettered Ph.D.