|

Anglican

Church of Our

Saviour

Florence, South Carolina + + + Services conform to the 1928 Book of Common Prayer |

The

Holy Slice

by Robert C. Harvey

|

Anglican

Church of Our

Saviour

Florence, South Carolina + + + Services conform to the 1928 Book of Common Prayer |

The

Holy Slice

by Robert C. Harvey

The Canterbury Guild

Philadelphia

COPYRIGHT 1973 BY

Robert C. Harvey

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Printed in the United

States of America

Transcribed and

uploaded to the www with the author's

permission by Joe Sallenger,

Gofer-In-Chief for Church

of Our Saviour Anglican Catholic Church in Florence, South Carolina.

Foreword

The Holy Slice is a remarkable book which so engrossed me when I picked it up that I found it difficult to lay it down until I had finished it. You have to be an Episcopalian, I suppose, and one who is vitally concerned about his church, to appreciate this book. If you are such an Episcopalian, you will find it absorbing. In brief, it is about a fictitious bishop who ought to be "for real"! This bishop in the story believes that the Book of Common Prayer is not just a manual of liturgy but a program for Christian living, and Christian being, as the Church of God. And as you read this exciting story about him you realize that what he believes about the Prayer Book (when people actually believe it and actually use it) is wonderfully true. This is not only an exciting story, it is a testimony of hope.

Carroll E. Simcox

Table of Contents:

Foreword by Carroll

E. Simcox

I The Holy Slice

II Of Tyros and Politicos

III The Choosing of a Bishop [Danger: Men at Work]

IV The Shepherds' Trust

V Unwonted Change for Clergy

VI Lay Lib and Clerical Rebellion

VII Program for a Ministering Church

VIII Of Ghettos, Charts and Men

IX The Following of a Prayer Book

X Temptation to Be a Celebrity

XI The Touch of Pain and Death

XII A Renewal of Life

When a signal for recess was finally given, the delegates leapt from their seats like schoolboys. Anxiety and concern, held in check by their own timidity and Robert's rules, had turned many of them into quivering bundles of nerves. They welcomed the break. Now they could take a more active -- if indirect -- part in the proceedings. They poured out onto the sidewalk and promptly went into huddles.

To many of the delegates it was more than the choice of a bishop that lay in the next few minutes' balance. It was the fate of a diocese, and perhaps, for a generation or more, of the Church itself. Therefore this was the time to rip away the rhetoric and come to grips with honest truth and logic. Now was the time to find the real meaning of the Body. With many talking and few listening, the recessed convention was in an uproar.

Only two of those present seemed to prefer to be alone. Starting from different points on the sidewalk, each walked up the flight of steps that overlooked the avenue and took stock of the scene. Eventually they drew together. The younger man introduced himself with body English. He rolled up his eyes in mock horror and at the same time shrugged his shoulders. The other answered with a wry smile.

"If two bishops hadn't stumbled into each other at the zoo," observed the second, "this might never have happened. Right now you could be out on the golf course. I could be at home writing a letter to a friend."

"Really? What do you mean?" The younger moved closer and bent an ear.

"This diocese got its shape back in the fifties when the Bishop of New York accidentally ran into the Bishop of Connecticut at the Bronx Zoo. They met in the lion house, and both were tired from walking, so they sat on a bench outside while their daughters and grandchildren went off to the primate house to see how the baboons were running their church."

"What happened?" The younger man wasn't sure he liked the other's flippancy, but at least he seemed to be at ease. His light touch was a welcome contrast with the proceedings, which for two days had been marked by shameless politicking, with time out for congratulatory prayers to the Holy Spirit.

"What happened?" the older man echoed the question. "At the time they met both men were under pressure to divide their dioceses. Bishop McClure's was a real pressure. Connecticut was the biggest diocese in the Church, and it was more than he could handle. Bishop Stratton's pressure, I think, was more inside himself. He was miffed because Connecticut had more communicants than he did, and he was having a running battle with some of his suburban parishes -- especially along the Long Island Sound. So the strategy in that meeting was mostly Bishop Stratton's. He got McClure to split his diocese in half, and he gave up only ten percent. A few parishes in East Bronx that were too poor to pay much attention to, and a few in East Westchester that were so strong they were a pain in the neck. In that meeting Stratton got rid of an albatross and put himself back in top spot. With a little gerrymandering, New York was the biggest diocese once more. With the biggest cathedral."

While the older man was saying this, a brief frown had appeared on the other's face, "I kind of shudder to hear bishops talked about that way. You make them sound like hucksters dealing with so many sacks of grain."

The older man continued in a gentler tone. "I'm sorry. I guess I am too tough on them -- especially now that they can't defend themselves. The fact is that they were saints compared to the men we've had running our church affairs in the last few years. My trouble is that I knew them too well."

The two looked down on the sidewalk scene. The delegates, who at first had clustered into small groups, were changing their arrangements. Instead of unloading themselves on their nearest neighbors, as people do at cocktail parties, they were forming into larger groups, where some could hold forth, and where everyone could feel free to come and go. Having gotten their bearings once more, the psychic compass had swung from subject to object. The electioneering process was again in full swing.

The eyes of both were caught by several young girls who had come out of the auditorium. All were dressed alike -- in black miniskirts and white blouses -- in an obvious parody of the cassocks and cottas they had once undoubtedly worn. The youngsters were on hand with a vote of their own, and had been recruited as monitors and tellers. They moved deftly from one group to another, "Recess is about to end. Please be in your seats in five minutes."

A picking of brains

The older man took a pipe from his pocket and prepared to fill it. Since he seemed to be in no haste, the younger inquired, "Are you in a hurry to go back in?" "No." "Do you mind if I pick your brains a bit?" "Not at all."

"What's really going on in this diocese? I mean, what's the infighting all about? I'm fairly new here, and I'm afraid that's why my rector asked me to be a delegate. He's very good about it, but he makes it clear how he hopes I'll vote. I don't like the idea of being a rubber stamp, especially since I think many of the people in the parish might be against the man the rector's for. My name's Jim Bridgman, by the way, and I'm from St. Matthew's in Salem Center."

"I'm John Stratton, Jim, and I live just around the corner." The two shook hands, and as the young man's eyes framed the obvious question, the older continued. "Yes, Bishop Stratton was my older brother. When the new diocese was formed I became its chancellor and held that job for a number of years. I know my brother hoped to keep his finger in the pie through my connection, but it never worked out. I found myself becoming a stranger in the church I'd grown up in, and when it became apparent to me that in my official capacity I was serving someone other than God, I gave up every office and became a plain communicant. I'm not even a delegate here," he added. "I just came as an observer."

By now the people below had all but disappeared. A few were taking a last drag on their cigarettes and stamping them out as they returned to the hall. Jim Bridgman took advantage of a moment's silence to bring his new acquaintance back to the question. "Tell me what the real issues are, and why the diocese is in such a turmoil. And tell me what connection there is between all this and the meeting at the zoo." The questions tumbled out in a cascade, and as he said this he waved his hand toward the auditorium where the delegates had reconvened.

The hijacking of a diocese

"I'll tackle the last one first, if you don't mind, because it gives me a good place to begin. I only mentioned the meeting because it was there that the two bishops actually made their decisions to establish a new diocese. But as soon as it was created the whole thing was hijacked by a group of men in the national headquarters who'd been pushing for a new diocese all along. They designed the diocesan structure. They outlined the programs it would follow. They got their own man in as bishop. And they actually recruited his staff. In fact," he added, "some of those men are on that staff right now. When the recent shakeup was about to take place, it began to look like the ax might fall on some of them. None of them got it because all were too smart; they dreamed up a new project and three got themselves transferred to the diocesan staff. And in the process they added to the tensions that have built up here between the lay people and the clergy."

"Is that what we're really facing? A division between clergy and laity? Is that what the issue is?" Bridgman had the look of a man who is on the brink of a discovery.

"No, not really," came the response. "There's a big difference in viewpoint today between the laity and the clergy, and this is an important issue if it's personalities that you're concerned with. But the real issues are more basic than that. There's the question of function and purpose in the orders of the ministry. There's the question of what the Church is supposed to be and what its mission is. Behind them all, I think, is the question of authority."

The younger man searched the other's face, trying to frame a question whose answer would be neither so profound nor so abstract that he might fail to grasp its meaning. At length he hit on one.

"Tell me, sir, what the plan was that the men at headquarters cooked up. And tell me why the people in the diocese were not alert to the dangers that might be hidden in it."

"I can give you an answer to the first, at least. The men on the national staff had a plan that was clear and persuasive -- and as secular as they were themselves. They were one-worlders in their mental outlook. They were socialists in their political and economic outlook. And like liberals in every field, they had no understanding of what St. Paul called "diversities of operations" -- that is, of the importance of differences in form and function. Being typical staff men, they had only contempt for the laity and for clergy who were pastors, so they hustled this plan for all they were worth. They used the usual jargon about dialogue and consensus and participatory democracy, and they paraded their captive laymen under banners of love, but these things were just tools to achieve their ends. When they got their way, people soon saw how phony the whole thing was. That's the cause of the tension, Jim. Not issues. Issues are important, but most people are only vaguely aware of them. The thing that hurt was the way the radicals used their power to dominate the Church. They changed it into something most people don't want it to be. And what's more important, into something that God may not want it to be."

A reason to stay on board

"I'm surprised you haven't walked out, Mr. Stratton. Or transferred to a church in another diocese. You could easily do that, living where you do."

"I've never considered that, Jim, and for two reasons. One is that there's a real Church behind the play church these fellows have built. The other is that I know what's wrong. Most people who have walked out in discouragement have known that something was wrong, but they didn't know what it was -- and that's the thing that bothered them most. All they knew was that the Church, as it was getting through to them, no longer came up to their highest expectations. I know what's wrong, and because I do, I think I can help God by staying on board and trying to put things to rights.

"Now, Jim," he continued, "let me get back to your earlier question. What the planners wanted was to create a new diocese by carving up several of the older ones. That way they'd have complete control; there'd be no past history on the local level that all the parishes would have in common. Another thing they wanted was a diocese that included two or more states. They were hipped on the idea of regionalism, and they wanted to link up Church and State in such a way that the Church could throw its weight around in the political and social areas. They felt -- as I do -- that much of our urban troubles come from outdated arrangements for political authority. But they felt -- as I do not -- that the Church's main task is to transform the world -- and not its members."

At this point the younger man felt able to make an observation of his own, "What you're telling me, Mr. Stratton, is that the meeting at the zoo wasn't really vital at all. Those two bishops didn't have much to do with what happened after that, did they?"

"Quite right. They were the finger that pushed the button, and the machine did all the rest. And believe me, they'd turn over in their graves if they could see what was happening now.

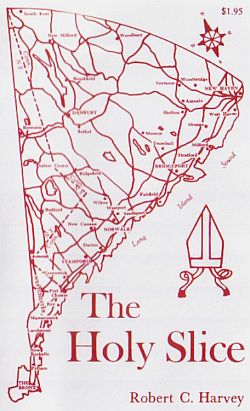

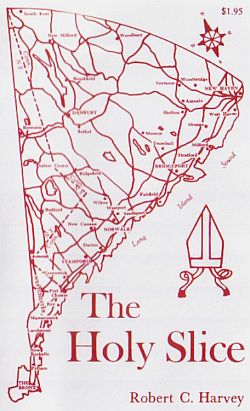

"There was only one thing they did that day that the staff men hadn't planned. It was to map out the actual boundaries of the diocese. That was because when the bishops came up with their plan, it fitted right in with what the others had been pushing. They knew they couldn't get the whole metropolitan area in one regional diocese, so they settled for what they called 'a metropolitical slice.' My brother and McClure couldn't buy that idea, though, and they gave the diocese a nickname of their own -- the Holy Slice."

Plotting the metropolitical slice

Here the older man chuckled, "It was comical the way they carved it out. Arthur used to tell it this way, 'Connecticut turned to me and said, "Okay, New York," -- they used to call each other Connecticut and New York -- "You tell me how you'd map out this diocese, and see if I don't go along with you."' So they got McClure's auto maps and spread them out on the hood of his car, and pencilled the boundaries. They ran along what's now the

Cross Bronx Expressway to the Bronx River, then up to the city line, then over to the Hutchinson River, then up the parkway to Saxon Woods, then in a line some fifty miles to South Kent, then along an arc down to the Quinnipiac River and the Sound just beyond New Haven. And that was it. My brother gave me the map and I still have it on the wall of my study. It shows the exact bounds of the present diocese -- all except for one thing."

"What was that?"

"I discovered it just recently, and it made me realize that the fellows downtown had gotten in the last word after all. The way the bishops arranged it, the focal point of the arc was the cathedral on Morningside Heights. This was because the cathedral was supposed to serve both dioceses. But when I realized there'd been a change, I plotted the focus, and guess where I found it?"

"I couldn't. Where was it?"

"The United Nations. How d'ya like that?"

The other was silent.

Straiten concluded their discourse. "I've never figured out whether the focal point was intended to be the General Assembly or the Think Room where they have that little altar with nothing on it. It would make a difference, you know."

Just then several people emerged from the auditorium. One, seeing Stratton on the landing above, called up, "Gosh, I'm glad that's over."

"What happened?"

"One of the speakers threw a fit while he was talking in the microphone. The next one started cussing and a man slapped him in the face. Everybody's tied up in knots, and I think the chairman must be a basket case. Anyway, the convention is adjourned until a month from today. "

That evening the phone rang in an apartment near the cathedral. The occupant was an arm's length away, "Judge Stratton speaking."

"This is Jim Bridgman, Judge Stratton. Are you the man I met today at the diocesan convention?"

"Yes, I am, Jim. What can I do for you?"

"Well, as I was driving home it occurred to me that you could be of help to a lot of the delegates at that convention. I'll bet that half of them don't have any more idea than I do of what's at stake. And I'll bet that there are a lot who are uncomfortable at the possibility that they're being used as pawns. I'm wondering whether you'd be willing to speak with as many as I could get together -- to tell us what the issues are and to explain the different factions that are jockeying for power. It seems to me that most of this is being kept under cover, and that in all honesty we ought to bring it out into the open."

"I certainly agree with you, Jim. That's the way it ought to be if the Church is really a household of faith."

"What I had in mind was two or three sessions to be held in different parts of the diocese. I'm not thinking of a discussion group but rather of a listening group, where people can hear what you have to say and can ask questions of you. I would simply want to have better informed delegates, and to have us get our information from someone we could hope to trust."

"I'd be glad to do that, Jim, although I'd prefer not to have any part in organizing it. It should be your idea -- not mine. There's one thing that I would insist on, however, for myself and everyone else. It is that this should not be a forum for discussing candidates or pushing their cause. Our concern should be the issues and problems that the diocese and the Church are confronted with."

"That's exactly what I had in mind, judge. I thought I'd draft a letter to the delegates and get your approval. Then, tomorrow, I can have my secretary send it off."

"Have you given any thought to where you're going to get their names? I doubt if you could get them from the diocese or from the secretary of convention."

"I was hoping you could give me some suggestions on that."

"I can. I have here a copy of last year's convention journal. It has the names and addresses of the wardens of every parish. If you wrote to them and told them what you propose to do, I think they might be glad to pass your invitations along to their delegates."

A course in "where it's at"

The following day Bridgman sent a letter with an announcement of Judge Stratton's talks to every warden in the diocese. The result was gratifying, and nearly a hundred people indicated their intent to be present at the talks. The Stratton name was well known, and it seemed appropriate that a brother of an earlier bishop, himself a judge and former chancellor of the diocese, should give the delegates the benefit of his knowledge of the Church and its affairs.

There was at least one man who was offended with the idea. At the first meeting, held at St. Bede's in the Bronx, a young priest arose. Interrupting Jim Bridgman as he was calling the meeting to order, he said, "Mr. Bridgman, I'm new in this diocese, as you are, and I appreciate your desire that we all know what we're doing. But there are two things I dislike about the method you are using, and I decided that, even though the clergy weren't invited, I'd better come with my delegates. The first is that you went around me to get at the delegates who are representing my parish. The second is that you didn't even clear this with the diocese." As Bridgman began to reply, the cleric finished hastily, "I know you haven't cleared these meetings, because I called the diocesan office and asked. They had heard nothing at all about them, and I can tell you they were plenty upset."

Bridgman took some seconds in replying, "Well, I'll tell you, Mr. . . . er, I'm sorry, I don't even know your name." "Father Smith-Jones," the other filled in, "of St. Peter's on the Parkway, in the Bronx." "Father Jones, as you say, I didn't call the diocese. The fact is I didn't even think about it. If you want an excuse, I was rushed. There was a very short time to arrange and announce these meetings. But besides that, I'm a layman, and I was taking advantage of what I suppose you might call layman's privilege. I don't know what the rules may be that govern you clergy and the diocese. But I never think of my relations with other lay people as being governed by rules, and I didn't think there might be any reason why delegates shouldn't get together. . . . There's nothing secret about these meetings." This last was added as Fr. Smith-Jones drew himself up to reply.

"Could I speak to this question, Mr. Bridgman?" All heads turned to Judge Stratton, who had not yet been introduced. "I think I know what Fr. Smith-Jones is referring to, and I'd like to discuss it -- but not for long, because we could spend all evening at it, and that's not what we're here for." Both Bridgman and the priest deferred to the judge, and he continued.

For one, obedience; for another, freedom

"I think Fr. Smith-Jones is referring to the canonical rule that puts a priest in charge, not only of a parish's spiritual direction, but of its administration. He certainly had the right to know about these meetings, and I owe you both an apology for not having suggested that the matter be cleared all around. But," and he turned to face Smith-Jones, "there's a distinction between your order and Mr. Bridgman's that you may not have given thought to. When you were ordained you took a vow of obedience -- among other things, to your bishop. When Mr. Bridgman was confirmed, he undertook no such vow. He simply promised to follow Jesus Christ as his Lord and Saviour."

Judge Stratton spoke briefly on the peculiarity of Anglican order, which puts its clergy in a nearly-Roman frame of order and obedience, while giving a distinctly Calvinist freedom to its laity -- enabling them to pursue their ministry quite free from churchly domination. He closed by quoting Bishop Gore -- like Fr. Smith-Jones, a high churchman -- to the effect that the difference between clergy and laity was not one of status, but merely one of function. With this out of the way, the meeting got down to the business at hand. The judge gave a lively and lucid review of the diocese' history, and of the problems that attended its birth.

The following week, at Norwalk, the judge talked at length of the new directions the Church was taking in the modern world, and of the issues and viewpoints that divided it. The contrast between his own knowledge and his hearers' was so great that few questions were asked. Yet at the meeting's close the men and women who were there seemed grateful for what they had learned.

It was not until the close of the final meeting, held in a parish in Bridgeport, that the judge was asked what kind of leadership and what kind of program he himself would like to see in the diocese. "I was hoping someone would ask me that question," he beamed. "Yet I'm not sure it would be proper for me to answer. What do you think?" Looking around the room, and receiving nods and murmurs of approval, he began to answer the question.

The judge's hope for the diocese

"My own feeling is that for a good many years the Church has been giving its main attention to matters that, worthwhile though they may be, are tangential to its mission. Our church press and our programs have been full of concern over freedom marches, college protest, new morality, the war in Vietnam, and we've neglected two things that seem to be insignificant, but that are the most important of all. Those two things are the Christian home and the parish. Both have been greatly weakened in the past generation, and I think we do harm to the divine economy if we put other things first in our priorities."

These words were met with vigorous signs of approval by several of his hearers, and Jim Bridgman noted that some who had heretofore seemed tense and withdrawn had suddenly relaxed. Now that the judge had doffed the academic role, they were finding that he shared their concerns.

Feeling this encouragement, the judge came more directly to his point of view. "Over the past fifteen or twenty years the Church has worked out a number of programs and -- officially, at least -- has given most of its thought and energy to their fulfillment. Unfortunately, all of these programs have dealt with the kinds of thing that catch the headlines -- the things that people talk about, and that are of political and social importance. None of them have had to do with the root things of our society -- the home and the local congregation and the development of the Christian individual. And because our Church leaders have neglected these basic things, their programs have never succeeded, and both they and their laity have been filled with resentment and anxiety."

Stratton paused for a moment, to let this viewpoint take shape in his hearers' minds, then continued, "What I would like to see at this point is the election of a bishop who will concentrate on the one program that never fails, and who will try to bring his clergy to attend to it. That program is the Book of Common Prayer."

Here the delegates, who had been listening with brightening faces, seemed puzzled. Bridgman addressed the judge, with the feeling that he was speaking for more than himself. "I wonder if you'd explain that, judge. I felt I was with you up to this point, but what connection can there be between the Prayer Book and a program of the Church?"

The BCP as a program for the Church

Straiten backtracked. "I'm sorry if I have bewildered you. I don't mean to imply that the Prayer Book is the kind of program you can turn on or off, or decide to use next year. Those are the kinds of program that Church staffs and conventions are always getting off the ground -- and that usually die a natural death. This is the kind of program you can hardly be against, because, like motherhood and the home, it gives the impression that God Himself has programmed it as a way of meeting human needs."

Pausing for this to sink in, he continued, "The Prayer Book is like any other program in the sense that men have put it together -- and, indeed, can take it apart. But it is divine in the sense that it is a means -- and it is the best means I have ever heard of -- by which men can daily come to Christ and share his presence, by which they can find his will and enter into his life. It is the means by which their lives are transformed, and it's the best means I know of for them to be strengthened to the arduous task of transforming the world."

Looking intently from one hearer to another, the judge remarked, "There's nothing new in what I'm telling you. But a thing that troubles me is that many of our clergy, if they ever were aware of this, have decided it's no longer relevant. They also have forgotten that the transformation of the world is the task of the laity, and that the transformation of the laity is the task of the clergy, and that this can only happen when the clergy give a great deal of time to God each day in prayer and Bible study and in worship and meditation -- all following the Book of Common Prayer.

The need to have a father in God

"Quite frankly, I would like to see the Holy Spirit give our diocese a bishop who would concentrate upon his flock, and not upon the world. I would like to have a father in God who would be a shepherd to his priests -- not one who was concerned with headlines or headline affairs. I would like to see one who would be willing to give up staff work altogether in order to attend to the personal needs of his people. I would like a bishop who would insist that his salaried clergy be out on the firing line, where they can do what Christ has called them to do, rather than attending to paperwork, programs and property. I would like us to be given a bishop who will be so sure of the Gospel, that he will be willing to operate with whatever his people provide, and who will delegate the temporalities to other, more practical men."

The judge stopped to take stock of what he had said. To anyone steeped in the ways of the Church, his words would seem to be those of a young man, rather than an old, and of an idealistic amateur rather than a professional. He decided to mention this, and let his hearers deal with it as they would.

"As some of you know, I was chancellor of this diocese for several years. I am not only a doctor of jurisprudence, but also of canon law. Yet I can apply to the canons the same description that Henry Ford did to the past when he said, 'History is bunk.' Lay people are hardly aware that there are such things as canons, and clergy use them either to get around the stark requirements of the Bible or to bully their lay people into letting them do what they want. If we would accept the authority of the Bible, and not of the Canons, we would recognize that bishops are intended to be servants and not presidents, and that rectors are supposed to minister to those in their care, and not exploit them to build up an institutional Church. The building and exploiting is Christ's job, and there'd be no end to the Church's growth or to the transformation of its members if the clergy would be faithful in living the Prayer Book life and in obedience to their vows. There would be such a massive outpouring of love and devotion from the clergy that the lay people could not help doing their part. They would respond with the same kind of love, and would carry it all over the world."

With these words the meetings came to a close. The get-togethers had accomplished what Bridgman had hoped, and everyone felt better prepared for the task of choosing a bishop. Judge Stratton had given them a thorough briefing without partiality for candidates, although he had expressed his wish for the Church.

A dark horse in the wings

A few days later the ninety-odd delegates who had attended the series received a letter from a woman who had been at the meetings. She began with an apology for what she was about to do -- suggest a candidate whose hopes for the diocese seemed remarkably like those of Judge Stratton. He was a parish priest who had given an address two years before to the diocesan churchwomen on the functions and strategy of the Church. It was one that had impressed many of the women who had heard it. Yet it had been offensive to the bishop, and had led to his being, ever since, the bete noir of the staff. A copy of the talk was enclosed, with the suggestion that this man might be a dark horse candidate for bishop.

On the same day a similar letter went out to a very different group. It was a coincidence that might have been of the divine providence, but at least was of no human devising. The group was the Laymen's League of the New York and Connecticut Shore -- an outgrowth of a Westchester group that in earlier years had been Bishop Stratton's bane. The league was made up of wealthy and forceful men who combined devotion to the Church with a dislike of liberalism in the clergy and in the Church's social programs. Being accustomed to the direct and open uses of power, they had only disdain for those who sought to achieve their goals by behind-the-scenes manipulation. They had no thought of influencing church policy through the canonical process of the vote. They used the power tool they were most familiar with -- money. Had any of them been questioned about this, they would have opined that their stand was more truly that of the Church as a whole than that of unrepresentative conventions by which church policy was determined. In this they might have been right.

One week before the convention was to resume, this letter went out to members of the League: "Gentlemen: The enclosed talk was given two years ago to a diocesan assembly of churchwomen. It got the speaker in hot water with the then bishop, and has kept him out of favor with the present standby administration. If you will read it, however, you will find that his proposals are closer to the objectives of this league than anything we could hope to find in another candidate. The Rev. Frank Roberts not only would reduce the diocesan staff. He would eliminate it. He would not only cut out the bureaucracy that hampers the Church in its mission. He would end the system of quotas and budgets that make it possible for bureaucrats and their half-baked programs to flourish.

"We must admit that we know very little about Roberts. But this document speaks for itself. It's likely that, if they took him seriously, many clergy would oppose his candidacy for bishop. But it's our understanding that Roberts is very well liked, even by those who regard him as an idealist and a babe in the ecclesiastical woods.

"One thing we do know. In the years before he entered the ministry, Roberts had a successful business of his own. In the relatively few years he has been in the Church, he has been a popular rector and an effective administrator. We are hoping you will make judicious use of these copies of his talk to advance Mr. Roberts' candidacy.

"We have tried unsuccessfully to get Mr. Roberts to speak at our meeting on the night before convention. He says that he is not a candidate and that, in any event, his evenings are booked. We like him, though, and think you will too. We suggest you attend his church on Sunday. Services are at 7:30, 9:15 and 11 a.m. It's Christ Church, Stamford, at the corner of Forest and Main."

III. The Choosing of a Bishop [Danger: Men at Work]

By the time the fourth ballot had been declared inconclusive, the delegates were as tense as they had been in the previous month's aborted session. There were eight men on the slate, and no change had occurred in voting balance since the first ballots of the earlier session. The jaunty air that had marked the opening of the day's business (and that had been described by the chairman as evidence of the Spirit's presence) had been replaced by one of apathy and fatigue.

Part of the trouble lay in the fact that the clergy and laity continued to go their separate ways. No nominee had captured a majority of either order, and those who had done well with one order had done poorly with the other. There seemed to be no hope of reconciling either the laity and clergy or the various factions within the diocese. The convention was at a stalemate.

It was at this point that Frank Roberts was brought into the running. A number of delegates who had no attachment to a faction had succeeded in passing a motion to reopen the nominations. They hoped that by loading the slate, the votes of the weaker candidates might be split, so that two or three strong candidates could emerge. Only one additional name was placed in nomination, however. It was the rector of Christ Church, Stamford.

As the diocesan politicos described it later, the nomination was a sleeper, and it came down on them like a ton of bricks. While fewer than half of the lay delegates were familiar with Father Roberts' name, many had given thought to his candidacy, and none had reason to be against it. Not many clergy were interested in him, but -- as it turned out -- many were willing to vote for him out of expediency. None of Roberts' fellow clergy disliked him, but none could identify him with their interests. He could not even be described with any consistency. Despite his radical stance on ecclesiastical function, he was regarded as more conservative than need be on matters of parish life. He was quite satisfied with the Prayer Book, and had never expressed the need to search for new forms of religious expression. His explanation was not satisfactory to everyone: his church was full every Sunday anyway, and he had more pastoral concerns than he could handle.

The clergy's candidates

Until Roberts' nomination, there had been four candidates who had been especially preferred by the clergy. They were: Canon Gildersleeve of St. Botulph's Chapel at Yale, Bishop Howell of Nashville, Gayle Stamper of television fame, and Father Inman of St. James, Greenwich.

Ralph Gildersleeve was the idol of intellectuals, both in and out of the Church. He was already a legend at New Haven, and had held professorships in the schools of law, drama, and medicine. A towering man who exuded charm, his handicap lay in his remoteness from ordinary people. He was admired, rather than liked.

Leonidas Polk Howell was the candidate of those who wanted efficiency as well as relevancy in the management of the Church. A descendent and namesake of the great Confederate bishop and general, he had been a unanimous choice, some years before, to be Suffragan Bishop of Nashville. Too many years on the national staff, however, had emptied him of pastoral concern, and too many years in the north had blunted the independent and traditional cast of the Tennesseean mind. When it dawned on him that a movement for a coadjutor was a way of shelving him, he began to negotiate for the berth he knew was opening in the New York and Connecticut Shore. He wanted to be back in the suburbs. He wanted to sink his teeth into the metropolitical slice.

Gavie Stamper was the darling of the younger clergy -- and because of their numbers was well ahead in the voting. Stamper was a new man, not only as a priest but as a Christian. He had been a lecturer at Columbia when he was baptized and confirmed. He promptly went to seminary, where he began his whirlwind career. Within months of his ordination, and while still a curate at the cathedral, he had emerged as an expert on communications. He was a prolific author of off-beat poetry, and an apologist for New Left causes. His afternoon program was always good for big names, novelty and frank talk on once-forbidden subjects.

Christopher Inman's coterie was made up of those whose lives had been altered by group dynamics. For the first five years of the diocese' life he had been the Executive Director of Education and Leadership Training. While at that task he had reshaped the minds of many clergy and of a number of lay people -- first with parish life conferences and then with group life labs and leadership training. The participants in these programs had been imbued with a new idea of Church and ministry, and in fact with a new sense of self. They had a whole new vocabulary, and respect for the new virtues of awareness and sensitivity. For this they were grateful to the director. They were the in-group of the diocese and Father Inman was the in-man of them all.

The lay people's candidates

The four candidates who were preferred by the laity were very different men. None was of more than local reputation. If any had gifts that might have won him fame, he discreetly kept them hid. None was ambitious in the sense of wanting a dramatic ministry that would give him fame or lead to the furtherance of a career. In order of their voting strength, they were:

Archdeacon Snodgrass of Trinity Church in Norwalk, Father McGrath of St. Mary's Church in Bridgeport, and the Messrs. Westerveldt and McCannon of Poughkeepsie and Ansonia, respectively.

In Joseph Ward Snodgrass the diocese had a loving and beloved pastor, a middle-of-the-road churchman, and a practical man of affairs. He had been President of the Standing Committee, Vice President of the Diocesan Council, and long-time head of the Department of Stewardship and Evangelism. Both in the new diocese and the old he had been many times a delegate to General Convention. By now, however, he was regarded by many as too old and too conservative. He had nearly won the election seven years before, but the younger clergy thought him passe.

Jerome McGrath was the acknowledged leader of what both he and its detractors called the Biretta Brigade. A man of warm compassion and lively wit, it was generally agreed that he would have had an enviable career in the Church had he played his politics right. But he insisted on being an Anglo-Catholic -- and in a liberal, broad church diocese at that.

William Westerveldt and James McCannon were men whose views on Church and change were very like those of Snodgrass. They persisted in remaining on the slate, however, because of what seemed to be the Archdeacon's indifference to spiritual wickedness in high places. In their view, he was insufficiently militant. They also shared the distrust that people in smaller cities and towns have for those who live in the suburbs. McCannon had been an Army chaplain, and had left the service to go to a parish in Ansonia. His militancy was of an America first variety. He looked for a communist behind every cassock. Westerveldt's militancy, by contrast, came from personal hurt. He had been rector of a large parish in Danbury, but had gone to an adjacent diocese when his bishop proved to be, not a father in God, but a cruel and devious competitor.

The strategists' mistake

Because Father Roberts' nomination came at a moment of irresolution, and because his potential opponents failed to see it as the work of the Laymen's League, no effort was made to handle his candidacy. It was rightly supposed that he would have no appeal for the clergy. But it was wrongly supposed that he would have so little appeal for the laity that his name would be quickly stricken from the slate. The strategists' mistake was that they failed to listen to what the nominators were saying, and they failed to notice the impression they made.

The young man who nominated Father Roberts was a vestryman of his parish. He was no older than many of the curates present, btu he spoke with a conviction that curates seldom convey. He was unself-conscious and his attire was plain. His speech was entirely free from jargon. He did not even try to tell the kind of Bishop Father Roberts might turn out to be. Instead he described his rector's ministry. As he described it, Christ Church was a parish much given to prayer and searching the scriptures. It had a profound sense of the worship of God, and a wonderful love and affection stirred among its members. The parish had done remarkable things in the community, yet these came of grace; there was no conscious effort to be "involved." The finances were handled smoothly and without stewardly stunts; the devotion that Father Roberts engendered among his people had enabled them to be lavish with their gifts. As the young man talked about his rector, his face glowed with admiration. He felt privileged to nominate Father Roberts -- even if it meant giving him up to a more highly-thought-of ministry in the Church.

By contrast, the woman who seconded the nomination told of the kind of bishop Father Roberts might make. She told of the views he had expressed in the past, and of the opposition they had aroused. She described his patience in allowing the waves of suspicion to break over him, and of his faithfulness to his job in the midst of clerical tension. She was no parishioner, but rather a former president of the diocesan churchwomen. She was known to every priest and to most of the women present.

The seconding speech came to many delegates as manna in the wilderness. Having no commitment to any of the factions, they nevertheless had a commitment to the Church. They were troubled by the tensions that had enveloped the diocese while dark Whitcomb was the bishop, and that continued to mount after his abrupt departure. They were troubled about church members' lack of enthusiasm, not only for budgets and programs, but even for parish life. Mostly they were troubled by a wholesale withdrawal of lay people that seemed to stem from disappointment with their clergy.

A deadlock broken

When the delegates filed before the tellers for the fifth ballot of the day, there was a very evident change of mood. The atmosphere was charged with excitement, and with it a kind of militancy. This mood did not register when the clerical vote was announced. Dr. Stamper was now in second place, perhaps because some of the younger clergy feared a backlash. But their vote had gone to Bishop Howell, showing a continued preference for the Establishment. Father Roberts, the newcomer, stood in sixth place out of nine. In the clerical vote he had topped only Gildersleeve, Westerveldt and McCannon.

When the lay vote was announced, there was a stunning surprise. Seven of the original eight candidates had lost ground. Canon Gildersleeve had lost nearly half of his vote. Father Inman had lost more than half, and Archdeacon Snodgrass' percentage had dropped from thirty to twelve. All of their losses had gone to Father Frank Roberts. There was an audible gasp when it was announced that he had been given forty percent of the lay vote.

The delegates' decorum turned into pandemonium. Everybody talked but nobody moved. Even before the hubbub had calmed, three names were withdrawn from the slate. The Messrs. Westerveldt and McCannon made the request for themselves. Canon Gildersleeve, in absentia, gave his withdrawal through his nominator.

A twisting of arms

During the recess between the fifth and sixth ballots, the Laymen's League played its trump. As the sidewalk huddles began to break up, fifty clergy were accosted by delegates whom they did not know, but who addressed them by name and in an offhand manner, "Father (or Mister) Soandso, I hope you're not going to vote for Howell (or Stamper or Inman). If you do, I'm afraid this will happen all over again in another year or two." The electioneering was done, not by the League's members, but by bookkeepers and clerks and pensioners. Some were from hard pressed small town churches. Some were from inner city parishes, and explained that they were trying to keep, not blacks, but the wolf, away from the door. Some were persuasive, while others were full of dire predictions. In every case they were urging a vote against an Establishment man, and in no case was Father Roberts so much as named.

As it turned out, even the most urbane cleric was open to the fears of the moment. Only one faction seemed able to weather the hopes and fears expressed in the electoral give and take. These were the Anglo-Catholics, who knew what they believed, and who saw the relevance of their faith to the present event, and who were under no psychic pressure to be on a winning side.

When the sixth vote was counted, Frank Roberts had been elected. He had received a majority of both orders' votes. The lay vote in his behalf had gone from forty to seventy percent. The clerical vote had leaped from nine to fifty-two. Even more than previously, the convention was in a turmoil. A few were beside themselves. Many were relieved. Most, however, were too perplexed to feel any joy over the election's end. They did not know by sight the man they had voted for. One of the most troubled of all was the chairman, who was presiding in the absence of a bishop. Canon Weatherbee was known to be partial to the election of Bishop Howell.

As the chairman turned to consult with others on the rostrum, a spontaneous cry came from the floor, directed towards the balcony, where Father Roberts was seated with his delegates. It was a cry to go to the fore. Roberts threaded his way through the stairways and aisles until he reached the platform where the chairman was seated. After a brief consultation with Canon Weatherbee, he turned and was introduced by the chairman. There was a brief applause and a long silence.

An office unsought -- and unwon?

Roberts looked about the hall as if searching for some sign of recognition, searching for something to say. He was pensive and unsmiling -- hardly giving the impression of one who has won a victory, or upon whom an honor has been bestowed. "My friends, members of the convention," be began haltingly, "I'm overwhelmed by this. You're asking me to take an office that we all give a lot of thought to, but that no one should ever seek. And you've chosen me in a way that astonishes me more than it has astonished you." Here he paused to collect his thoughts, "I'm not so much concerned as to whether I should accept the election as to the propriety of the election itself. It has been so sudden. There have been so many emotional forces at work, and rational forces as well. There have been a lot of pressure groups, and, as you know, some pretty bitter in-fighting. I don't know who or what is in back of my nomination, but if I should accept your offer, and should want your support for more than a day or a week, it should never look like this election was rigged. Therefore I should like to speak to you for a few minutes about how I look upon the office of a bishop and how I see our needs. Then, if it's all right with the chairman," and here he looked at Canon Weatherbee, who nodded his approval, "I'd like to give you a half hour's recess and then have the ballot cast once more.

"I know that in the election of a bishop it's customary to have a final ballot, which is supposed to be unanimous. I'm not thinking about that kind of ballot. I'm simply asking you to think once again whether you would like to have me for your bishop, and I'd like you to have the feeling you're not being stampeded. If you repeat your offer, I think I should accept. But if I am turned down by either order I shall take it as a sign that I should withdraw from the ballot."

Father Roberts then went on to tell of his life and his background, of his ministry in the Church, and of his outlook on the episcopacy and the diocese' current needs. After a few minutes he concluded. The convention was given a recess, and Father Roberts found himself in the center of a large number of delegates. Some came to offer their congratulations, but a larger number came to hear him further and to ask him questions. They were taking him at his word.

When the final ballot was cast, the delegates showed a calm that had been missing up 'til now. The sentiment seemed to be that the die was cast, and that Father Roberts was both acceptable and accepted. The results were as expected, and yet his approval was far from unanimous. The lay delegations voted in Roberts' favor by ninety-two percent. The clerical order was more conservative. His fellow priests gave him sixty-two percent of their vote.

A sense of wonder still possessed the convention's members as they filed out of the auditorium and into the cathedral for prayers. Father Roberts' own prayers included the hope that he and his clergy could be one. As he told of the election to his thrilled and disbelieving family that night, it would be some time before it could be seen whether this was the work of man, or whether the Holy Spirit had really been at work. The representative process had been followed, at least. If neither the people of the diocese nor the clergy had really chosen him, perhaps in time to come they might act with one accord. If the election was dubious, perhaps the Spirit of God might help him grow up to the office.

It did not take Bishop Roberts long to decide that there was practically no evidence that his election was the work of the Holy Spirit. God's part in the affair, if any, was beyond human scrutability. There was plenty of evidence, however, that the election was the work of man, and -- if you took the bishop's word for his existence -- the work of Satan as well.

It was not long before the rumor mills that form, more than do conventions, the mind of the Church, discovered a connection between the Laymen's League and Frank Roberts' election. (To be sure, the mills ground chiefly for clergy, since it was they alone to whom diocesan affairs were a matter of daily concern.) The judgment was based upon a hundred little discoveries that were shared and passed around. In some cases the clergy who had switched their votes took the trouble to identify those who had influenced them and to find what their connections were. In other cases they got some feedback from neighboring clergy, in whom their lay delegates had been more than ready to confide. In most of these cases the facts were quite real and the inferences quite valid. The Laymen's League had indeed done a clever job of influencing the election without revealing its hand. But even when the facts corroborated one another they did not add up to truth. Bishop Roberts was not a pawn of the Laymen's League, nor did that body ever try to capitalize on its stratagem. The effect of clerical gossip was merely an increase of suspicion and disunity.

His first mistake, Bishop Roberts conceded, was in asking for a more conclusive ballot. He had wanted to be magnanimous, and to allow the delegates a chance to be more concerned with their interests than with their emotions. But he had failed to appreciate that such a ballot should come a month -- and not a half hour -- later. If he had even been conventional enough to go along with the "unanimous" ballot, the delegates could have been let off the hook. They would have engaged in the harmless celebration of a myth, and would have gone back to their partisanship with little sense of loss. As it was, Frank Roberts had made the clergy believe that, on that final ballot, they were participating in something real. And when the result proved inconclusive, they were filled with recrimination. Those who had voted against the new bishop -- and they were a third of the total -- were against him still. Those who had switched their votes felt even worse. They had surrendered cheaply to their desire to end the tensions in the diocese. And they had given in to fatigue in wanting to get the election over with.

To be -- or not to be -- a bishop

Less than a month after his consecration, Bishop Roberts began a series of meetings with his clergy. As he expressed it, he was supposed to be a shepherd of shepherds, and this was an impossibility if he did not have the respect and trust of his clergy. It was also an impossibility if he gave priority to matters that came across his desk. He realized that his clergy might not want a pastor, and that they might prefer a bishop whose interest was "larger than parish" affairs. But this would have to come out in the wash; it was not in the cards right now. The bishop felt strongly that he must know his clergy and they must know him. They must be given the chance to bring their concerns out into the open, where they could be dealt with honestly and reasonably. Their private concerns would have to wait until they could see whether he would share their common concerns -- or whether he would even listen.

The first meeting was held at Orange, and included the fifteen clergy of New Haven archdeaconry. It seemed good to start in New Haven because this was the most self-contained of all the archdeaconries, and because the New Haven people both valued and resented their remoteness from the rest of the diocese. Some of these clergy were vigorous intellectuals, and the bishop hoped this meeting might set a tone for those that would follow, both in New Haven and elsewhere.

If any discussion had taken place among the clergy before the bishop's arrival, it was discreetly hid. After the bishop had described his purposes in initiating the meetings, he asked for suggestions for an agenda. There was an awkward silence, which was broken by the Orange rector, who was playing the host. His question seemed to have been framed by a committee, rather than by an individual. The bishop wondered about the agenda, but knew he must deal with this first.

"I'm not sure what you're driving at, Sam. Are you asking about my views on the matter of diocesan staffs, or what I think is likely to happen?"

Expression of distrust or concern?

"Well, bishop, it's both. We have this concern for the men who are on your staff. What do you propose to do with them? How will they make their living? And we're also concerned for the work your staff has been doing. How will it be continued, or will it? What will become of the programs that all of us have been so deeply involved in? Will we be able to keep on showing our concern for the world around us, or will we not? And what about the image we've built up in our various communities? Will we continue to be known as an outreaching, loving, caring Church? Or will we be seen as retreating to a comfortable pew?"

It occurred to Bishop Roberts that this might be more an expression of resentment and distrust than a question demanding answers. And it could not be the expression of one man alone; Sam Lessing undoubtedly spoke for many others when he used the editorial we. He was giving the bishop a preview of an apprehension that might be found among the clergy for a long time to come.

"Sam," the bishop began, "I hope that nothing I've said will be interpreted as a lack of concern for the poor and the powerless. That concern is one of the great motifs of both the Law and the Gospel. And I hope that you will not take my opposition to having priests do staff work as a sign that the Church should not be concerned with social problems. I simply believe that a man who has been called and ordained by Christ as a priest should have the pastoral care of souls. And I believe that the Church's involvement with the world is chiefly a function of the laity. It is something that can easily be done -- and I think should be done -- without bringing the Church into the arena as an intervening body, where it has to throw its weight around and where it can only pretend to be of one mind."

Here he realized he was skating on thin ice. He might be surrendering whatever foothold he had in his hearers' esteem, but he thought it worth risking, that his clergy might know his mind. "I'm going to get away from your question for a minute, Sam, but if I should fail to answer it to your satisfaction I hope you'll bring me back to it later.

"When I was in college I had an art professor who had been one of the Bauhaus school in postwar Germany. Their slogan for architecture was one that I have since realized has been used by God Himself everywhere in His creation. It was the idea that form follows function. It's what made it possible for architects to break away from pretty facades and make buildings that were organic extensions of the earth on which they were built and of the people who lived and worked in them.

Form and function in the Church

"It's a curious thing that modern art should rediscover something that the Church has always known. Form follows function. It always does, and if you've forgotten what the function is take a look at the form. In all the essentials the Church has only a twofold form, and so has the ministry. We have one form in relation to our members and another in relation to the world. We have one type of minister who belongs chiefly to the Body and another who belongs to the world. The Church has the form of a Body mainly when it is worshiping God and when it's dealing with the things that are eternal. The clergy's function is ministering in the Body and caring for their members' spiritual needs. At this point the laity are dependent upon the clergy in the sense that the clergy are channels for knowledge and power. But the ministry of the Church to the world is something else again. Here the laity are not dependent upon the clergy and are not answerable to the Church. The Church can speak with one mind when it is 'in the Body' because it is dealing with the eternal verities. But it cannot speak with one mind about the world. And that is not only because the world is full of ambiguities. It is also because the ministry of the laity -- which is the ministry to the world -- requires the Church to speak with as many minds as it has members."

Bishop Roberts said these things as simply and as honestly as he knew how, yet as he said them he had the feeling that he was not getting across to more than one or two. He was not listening as he was supposed to; he was lecturing his clergy. He acknowledged this, adding that he had only one more thing to say, "You know, this dedication to 'involvement' that's found among the clergy really belongs to the laity -- and it disappoints us if we can't see it. But I think we do our lay people an injustice if we conclude that because we can't see their involvement, it isn't really there. Lay people are not obligated to give us an accounting of their good works, you know. And while we might like to tell them how to run their business, our function is to mediate Christ."

Here the bishop cut himself short, apologizing for the lecture. When the clergy sensed the bishop was determined to talk no more and was eager to listen, they began to open up. His relaxed manner and his readiness to hear made it obvious that he was willing to accept his clergy as they were, and that nothing they might say would be used against them. Over coffee and across the luncheon table the conversation ranged from baseball to Vietnam to film censorship, and the clergy found the bishop as one of themselves. He showed no conceits and seemed to care only that his clergy knew his opinions on the tasks and functions of the ministry.

A prelate out of date

Once they had found that their bishop had no "side," the clergy were ready to get back to discussions of the ministry. They did want to know his mind, and they wanted to know where he might lead them -- provided, of course, that they were willing to accept him as their bishop. George Briggs, who was curate in a slum church, remarked, "You know, bishop, if you had come to seminary and said these things, you'd have gotten nowhere at all. The students would have crossed you off as hopelessly outdated, and the faculty wouldn't have bothered to ask you back."

The other clergy held their breath, looking first at George and then the bishop. The latter snorted in amusement, and Briggs continued, "What I mean is, nobody seems to buy this bit about form and function any more. It might apply to architecture, but does it apply to living? The way I hear it is that those things belong to an outmoded view of life, and that the things that count today are similarities -- not differences."

Nobody spoke, so Briggs went on, "It seems to me that it's undemocratic for things to differ, and the idea of function makes them differ. It also seems undemocratic for one function to be subordinate to another. Why, for example, can't my wife be as good a priest as I?"

When Bishop Roberts responded, he seemed to be speaking only to the curate and to be unaware that the others were listening. "George, I think I follow you but I don't think you understand me in this matter of form and function. But would you agree with me that we are ordained as channels for God's love and healing power?" Briggs nodded his assent, and the bishop continued. "If you do, you must agree that even channels have to have boundaries. Rivers have to have banks. Pipes and power lines have to contain what they carry, and the current has to have direction. Right? Then do you also agree that if we are to be channels or intermediaries what we do is significant only if it's done in a way that God has determined?" Briggs looked a bit mystified, but continued to nod. "And, George, you must agree with me that if one function in the Church seems to carry more prestige than another, it's something man has given it -- and not God?" Here the curate nodded vigorously. "Then if differences in status are caused by seeming differences in the importance of function, might we not do well to get rid of the idea of prestige -- instead of the idea of function?"

Here the bishop realized he was overshooting the mark, and he stopped talking. His eagerness kept betraying him, for he would prefer to have silence -- rather than words -- speak for him. The talk turned to small and diverse things, and only after some time did the host rector return to what had been on his mind at the beginning.

"Bishop Roberts, I wonder if we could get back now to the question I asked you at the beginning. The one about the clergy on your staff."

"I don't know how to answer that, Sam. Partly because I don't know the answer and partly because if I tried to give you one it would neither express what I mean nor what you wanted to hear. Why don't you try putting an answer in my mouth?" Father Lessing looked startled, so the bishop added some encouragement, "I know this is a matter that concerns you greatly, so tell me how you'd resolve it. If you were I," he added.

Samuel Lessing hesitated. He was not sympathetic to what he knew of the bishop's ideas, and was not sure how he could project an answer in the other's mouth. "Well, ah ... I was thinking, ah ..." He found he could not play the role, so he blurted out what was in his mind, "Bishop, I'm just concerned for the priests who are on your staff, and I'm concerned about what would happen to staff people and to programs all over the country if your ideas should take hold in other parts of the Church. The laity are not very sympathetic to these programs, you know, and it would be all too easy for ideas like yours to spread. This is why I'm concerned. What would you have these staff priests do? Where would you have them go? The Church already has more clergy than it needs, and we've got to have something for them. You can't just take a man who's been working at a thing for years, and dump him out in the cold, saying to him, 'The thing you've been doing no longer has any value.' "

Make-work fallacy creeps into the Church

When the bishop answered, he did so very gently, "I have no intention of firing anyone, and if the diocese buys my ideas -- which it very well may not -- I have no intention of bringing their work to an end. I just don't happen to believe that a man who has been called by Christ and ordained to the priesthood should be ministering to programs or paperwork -- or even to an institution. Our Lord has called us to a personal ministry, and when we get the kind of concerns that showed up in the sixth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, we should do what the Church did then. We should delegate it to someone else, and not allow our ministry of sacred things to be swallowed by the mundane."

"I don't think any of us can be in disagreement with you on this. Bishop Roberts, but let's get down to specifics. What can these men do? There are no jobs available to them, and as you say, they were called and ordained by Christ."

The bishop looked up, first at Father Lessing and then at the others. "Sam, I'm going to ask you -- and all of you -- to make the same leap of faith you made when you accepted your vocation. You committed yourselves to God without any other assurance than that of faith that he would take care of you -- and by take care of I mean employ. Is this not so?" The bishop looked about and the clergy nodded their assent. Then if you have made this leap of faith for yourselves, why not do the same for other clergy, and for the ministry as a whole?" His point was well made, for by their expressions some of his hearers had never thought of this before.

The pertinence of vocation

The bishop continued, "Don't take me for a lightweight. I know how serious the situation is. We simply have more clergy than we have jobs for, and it's a situation that was caused largely by the military draft. But there's an answer, and I think we may find it in the idea of vocation. A number of our priests are men who went to seminary to avoid conscription, and it must be obvious that some of them were never called. It seems to me that the men who have a genuine sense of vocation will persist through the present difficulty and will come out on the other side. On the other hand, those who were not called and who nevertheless are exercising a ministry will discover their want of vocation. (Either they will find it for themselves or someone else will point it out to them.) Those people will gradually leave the ministry and will go into the other professions where ambition is a recognized qualification. Then things will settle down to normal and we shall once again have a ministry of men who have actually been called by Christ.

"What I am leading up to is this: I don't think we can rightly employ clergy in jobs to which no one was ever called. It is my hope to put all our priests in a ministry of service to people -- either as pastors to the laity or as teachers to the clergy. If we do this -- and if these men are industrious and obedient to their vows -- the problem will disappear. You can't have a devoted and faithful clergy without having a growing laity. When the shepherds begin behaving like shepherds, the Church will end its stagnation and will begin to grow by leaps and bounds. It will no longer spend time worrying about its image, but will begin to be concerned for its members. The change doesn't begin with the Church, or with the laity either. It begins with you and me. We have only one set of marching orders, and it comes from Christ Himself, 'Feed my sheep.' "

As he left the meeting, Bishop Roberts had the feeling that a few, at least, had given respect to his words. Even some of the young ones, like George Briggs. He wondered if it was because he could have spoken to them as an authority figure. If so, it could not have been because of any sense of authority in himself, but because he insisted on pointing at an authority beyond themselves that depended upon no one for definition.

Stopping at a filling station for a tank of gas, the bishop picked up a copy that someone had given him of The Imitation of Christ. The frontispiece was a painting of Jesus that he had never seen before. Was it a Rembrandt? He doubted it, it was not that somber. Was it one of the Flemish painters? Perhaps. Whoever had done it had showed Christ as he ought to be seen today. It was a manly face, but showed the power and glory of God. It seemed to manifest the divine love, yet without doing an injustice to justice. In it the bishop saw a new face of one be had loved from boyhood. He breathed a silent prayer of homage, "Glory be to thee, 0 Lord."

The remainder of the first round of clergy meetings were in much the same vein. As the bishop talked with archdeaconry groups in Bridgeport, Norwalk, Stamford, Danbury, Westchester and the Bronx, he felt a sense of apprehension among his clergy. It seemed to be directed toward him, and to lie in a fear that the man they had helped to elect might become for them the agent of unwonted change.

The bishop's ideas of change, however, did not lie in innovation or experiment. Rather, they lay in a return to basics, both as the Church had always known them and as the majority of lay people seemed to prefer them. It had been the bishop's hope that he might guide clerical discussion to what seemed to him -- as to traditionalists everywhere -- the easily discernible separation of task and function in the ministry. He was quickly disabused of such an idea. Especially among the younger clergy, and among those in high-powered suburban parishes, there seemed to be no understanding of functional differentiation. Even the ideas of order and authority seemed to have disappeared, excepting as fluid things that depended upon the consensus of particular groups at particular times. Faced with this fact, the bishop decided to speak about roles instead of functions. He knew that for many of his men ought was a threatening word, and that vows were regarded as mythical, rather than something real. The idea of function was disliked because it suggested something from which one could not take a vacation. On the other hand, the idea of roles -- which could be put on or cast aside at convenience -- was an appealing one.

By the time he got to the Bronx, Bishop Roberts could sum up the approaches that had worked best in earlier meetings. He supposed his ideas would appeal to these particular clergy, for they were -- outwardly, at least -- the most ordinary men he had. Unlike the more ambitious and aggressive suburban clergy, these priests were matter of fact, down to earth -- very like the people to whom they were ministering. The bishop kept this in mind as he spoke to them.

Conflict between ministering and administering

"I should like to give attention," he began, "to something that lies behind the tensions that exist between lay people and their clergy. It's an ambivalence that exists within the ministry itself. When a man is placed in charge of a church he is given two roles that are in conflict with one another. As a pastor, he is charged with the care and support of persons. He must treat them as ends in themselves, requiring nothing of them and helping them to see themselves as objects of God's redeeming love. As rector he must act as a ruler and exploiter of persons, using them as means -- and not as ends. In one sense this exploitation is constructive, and is required by Christ Himself, when He commands us to carry the Gospel throughout the world. In another sense it is destructive, as when we manipulate our lay people to serve our own ends, and to aggrandize an institutional Church.

"Regardless of how we make demands of our members, however, we must face the fact that not every Christian has the psychic strength to be exploited. Many of those in our care are not only spiritual, but emotional, babes. They've got to be on the receiving end of a lot of ministering before they can be strong enough to minister to others. They've got to have a lot of confidence in Christ before they can discover that when they give themselves to others in His name they are not taking anything away from themselves.

"This conflict of roles is something that Our Lord has dealt with in His parables. He tells us that the good shepherd knows his sheep and calls them all by name. The good shepherd risks his life daily for his sheep. The hireling, by contrast, cares nothing for the sheep. His job is just a way to fill his stomach.

Shepherds who drive, shepherds who lead

"I've learned something recently that highlights these teachings of Our Lord. There was a striking difference in ancient times between the ways that Jews and gentiles handled their sheep. The gentiles always drove them -- and I mean that literally. Down in the fertile crescent, when they took their sheep from one pasture to another, they herded them with goads and with dogs they had trained to direct and harry the sheep. By contrast with the gentiles, the Hebrews didn't drive their sheep at all. They led them, and because the sheep needed and trusted their shepherds, they followed of their own wills.

"What makes this analogy more impressive is that the Hebrews' pastures were mountainous and the paths precipitous. The shepherds led the way, and if it proved safe the sheep followed. If the sheep chose not to follow, they got left behind, only to get lost or into danger. But they could count on it that when the other sheep were safe in the fold, the shepherd would come and find them. He was responsible for his sheep, but he respected them enough to let them go off on their own.

"If I can apply this analogy to our ministry -- and Jesus' parable demands this -- it is that our primary duty is shepherding, and not exploiting. We are charged with building up the Church as a community of faith, but we must do it by paying attention to the sheep as individuals, and not by thinking of them as a flock. If this seems to give value to the individual at the expense of the Church, perhaps we can see that it is best if Christ exploits the members of His Body -- rather than if we do. After all, it is He who can decide which ones are strong enough to give themselves to a ministry to others, and it is the Holy Spirit who guides and directs their way. This is why I feel that the time we spend in planning activities and in organizing our work and that of others is at best play-acting. We see ourselves in creative roles, and are in reality only building a play church. We are substituting towers of Babel -- albeit churchly towers -- for the wonderful works of God.

Constant function vs. transient role

"If I can venture an opinion on all this, it is that we have become so saturated with group dynamics that we've allowed ourselves to think of everything we do as being nothing more than roles. There is nothing that binds us -- nothing that commits us whether we like it or not. When we get tired of one role we put on another. This allows us to be priests one minute, public affairs experts another minute, and fund raisers in a third. It's not, I think, what God means us to be, and what is meant when we vow to lay aside the study of the world and the flesh. Priesthood, by its very nature, has to be one of the permanent things, like motherhood. Once you're in it there's no relief from its duties this side of the grave. There can be great joy in it, however, and a great sense of fulfillment, if it's accepted as a function given and empowered by Christ. It does more than anything but motherhood to bring God's will to bear in the lives and affairs of men."

By the time the second round of archdeaconry meetings had been completed, Bishop Roberts had begun to feel that he was getting his point across. If he had not yet touched his clergy's hearts, he had begun to touch their heads. They were beginning to acknowledge that the first obligation of their calling was the spiritual nurture of those committed to their care. They were moving from the pagan philosophy of total involvement (which, the bishop pointed out, was the basis for totalitarianism) to a dynamic that included detachment. A priest had to be detached from the world in order to be creatively involved with it. His detachment was a spiritual and psychological, as well as a social, need. The priest needed, in his time of detachment, to identify himself with the things of God, so that in the time of his involvement he could minister those things to a world that has no other way of getting them.

VI. Lay Lib and Clerical Rebellion